There are certain operas that demand a great deal of the imagination from their audiences. Salome, for example. The adolescent heroine is only 15 years old, but Strauss gives her some very intense notes to sing. You need to have a voice like Isolde’s, but you also have to be able to convince the audience that you are a very attractive and very young thing.

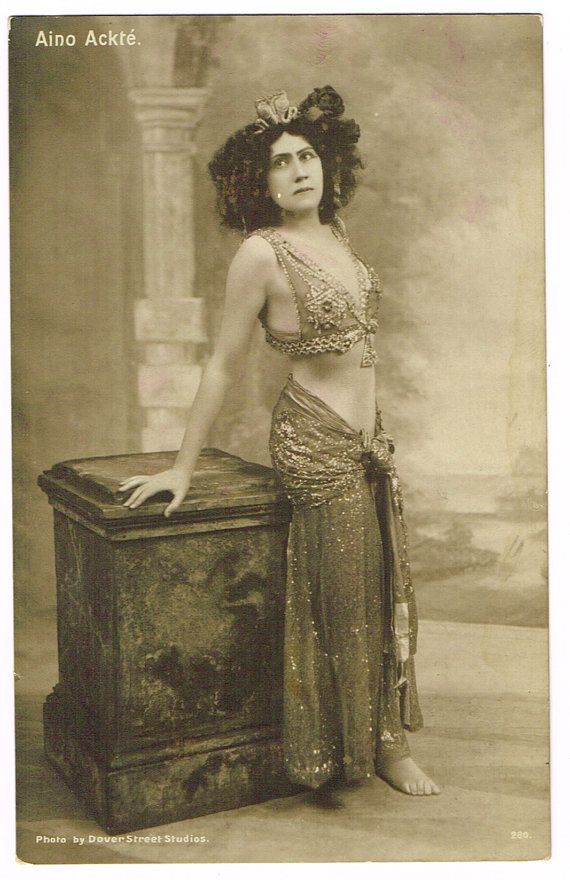

Strauss did not initially require all this – his very first Salome, who sang the premiere in Dresden(1905), Marie Wittich, was rather overweight. But Aino Ackté, a very popular Finnish soprano at the time and a very attractive woman, managed to convince Strauss that she was the only real Salome. She took ballet lessons and prepared for the role with the composer himself.

She sang her first Salome in Leipzig in 1907, becoming the first singer in history to perform the “Dance of the Seven Veils” herself. London (1910, under Beecham), Paris and Dresden (under Strauss) followed, and she set a standard that few singers would be able to match. Not that she performed the striptease in its entirety: under the veils she wore a flesh-coloured bodysuit, which suggested nudity.

The very first to emerge completely naked from under the veils, at least on stage, was probably Josephine Barstow, in 1975, first at Sadler’s Wells in London. Shortly afterwards, she repeated the role at the Deutsche Staatsoper in Berlin, in Harry Kupfer’s production, which was also performed at the DNO in Amsterda

Another problem that many directors (and the actress playing the lead role!) may struggle with, is the character herself. Is Salome really a dangerous seductress and sex-crazed nymphomaniac? Perhaps she is just a normal teenager looking for love and affection?

A spoilt girl who grows up in a loveless environment, where people care more about money and appearances than anything else? A victim of the lustful urges of her horny stepfather, who has great difficulties dealing with her own burgeoning sexuality? She, in her naivety, may believe that the “holy” man, with his mouth full of “norms and values”, can actually help her, but then she is brutally rejected. Causing her to seek revenge? Difficult.

And what to do with Jochanaan? The libretto explicitly states that he must be young and attractive, but try finding a bass/baritone with a big voice and an authoritative presence who also has enough appeal for a beautiful princess, who herself is the object of intense admiration and desire. It remains a dilemma.

CDs

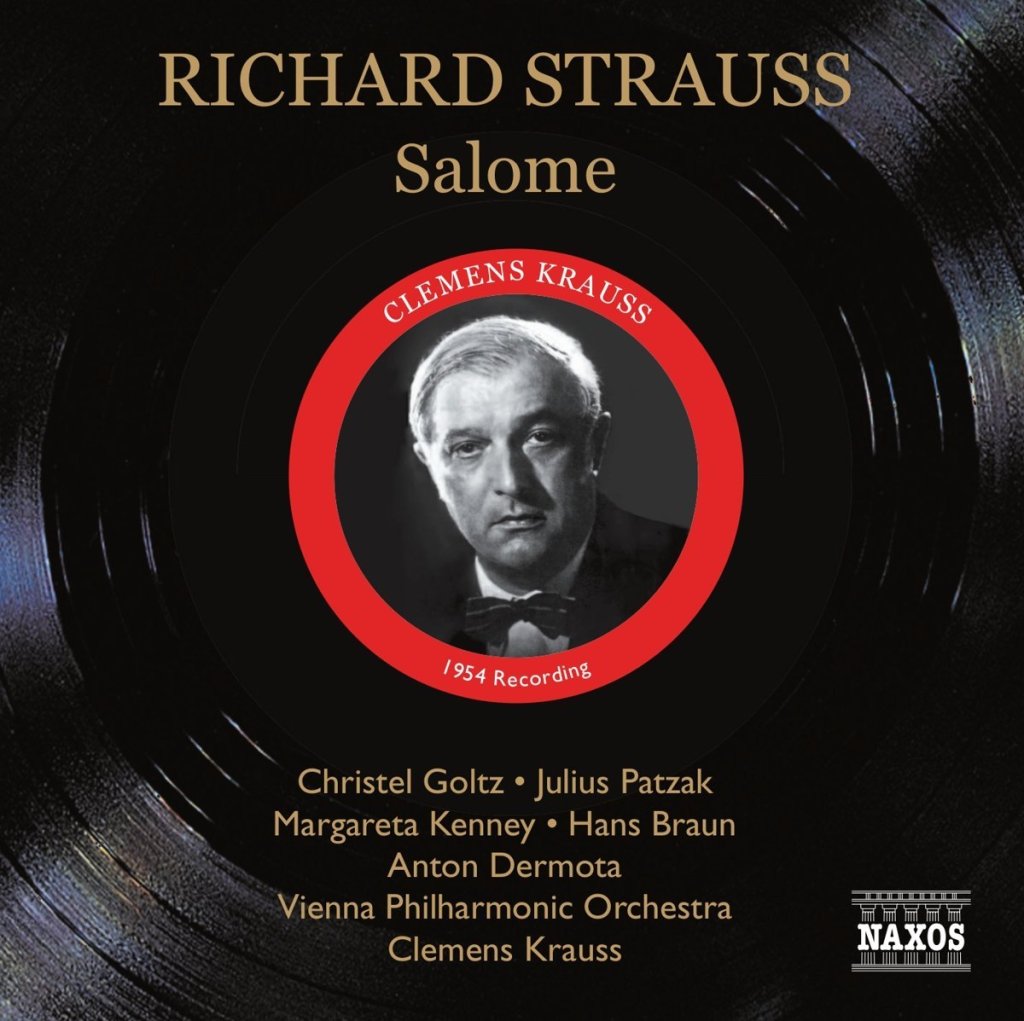

CHRISTEL GOLTZ (1954)

This recording may not be one of the best Salomes in history, but it is certainly special. Once you get used to the sharp mono registration, a whole new world of sound opens up to you, one that is unparalleled. The richness and colours of the Vienna Philharmonic at its best – I could

listen to this for hours. For that alone, I wouldn’t want to forgo this recording! Clemens Krauss belonged to Strauss’s inner circle; he also conducted the premieres of a few of his operas, and you can really hear that.

Christel Goltz is an excellent Salome. Self-aware, not very naive, really powerful,

and what a voice! Julius Patzak (Herod), Margareta Kenney (Herodias) and Hans Braun (Jochanaan) are not particularly remarkable, but Anton Dermota’s soulful and tearful Narrabothmakes up for it (Naxos 8111014-15).

.

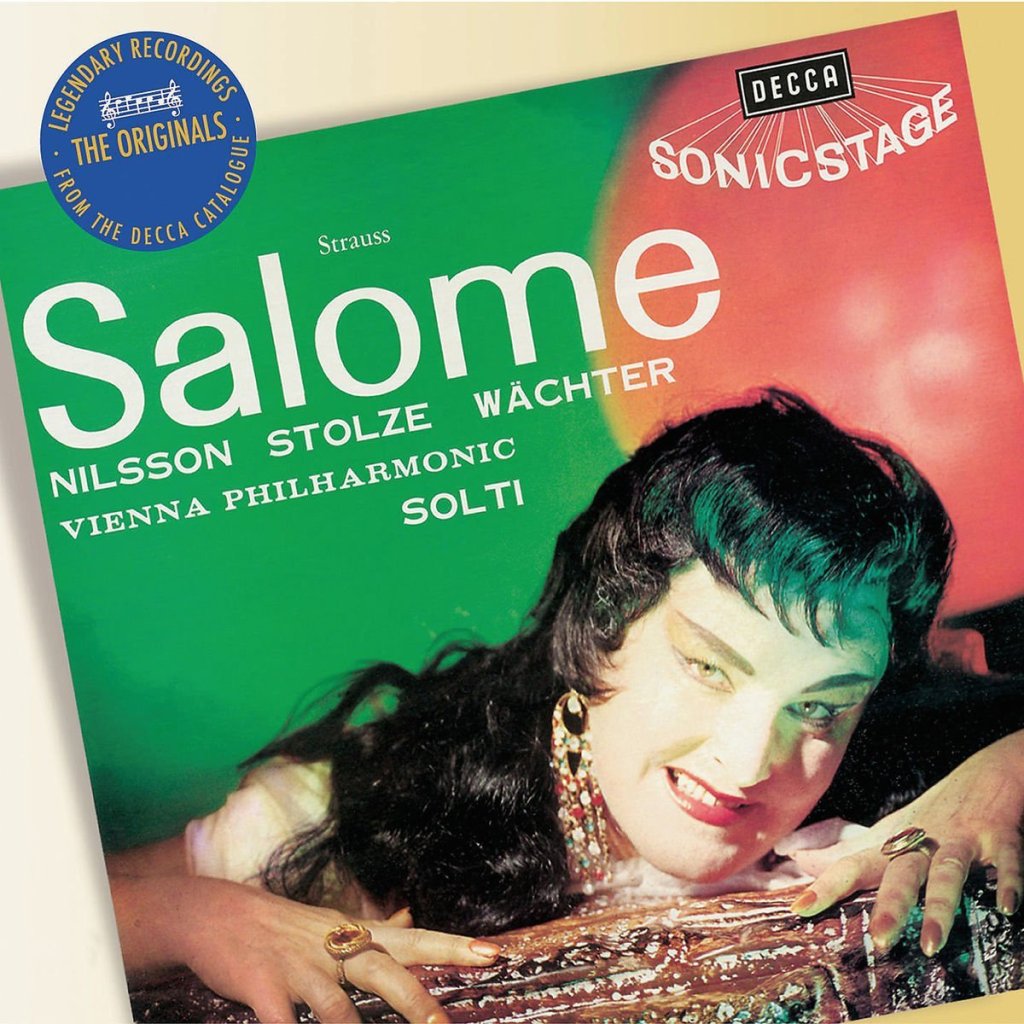

BIRGIT NILSSON (1962)

This recording is considered legendary, but it has never appealed to me. Nor have I ever been impressed by Birgit Nilsson’s interpretation of the title role. Nilsson has a powerful voice, but she is neither seductive, nor erotic or naive.

Eberhard Wächter shouts himself hoarse as Jochanaan and Waldemar Kmennt as Narraboth is nothing short of a huge mistake. What remains is Georg Solti’s exciting conducting

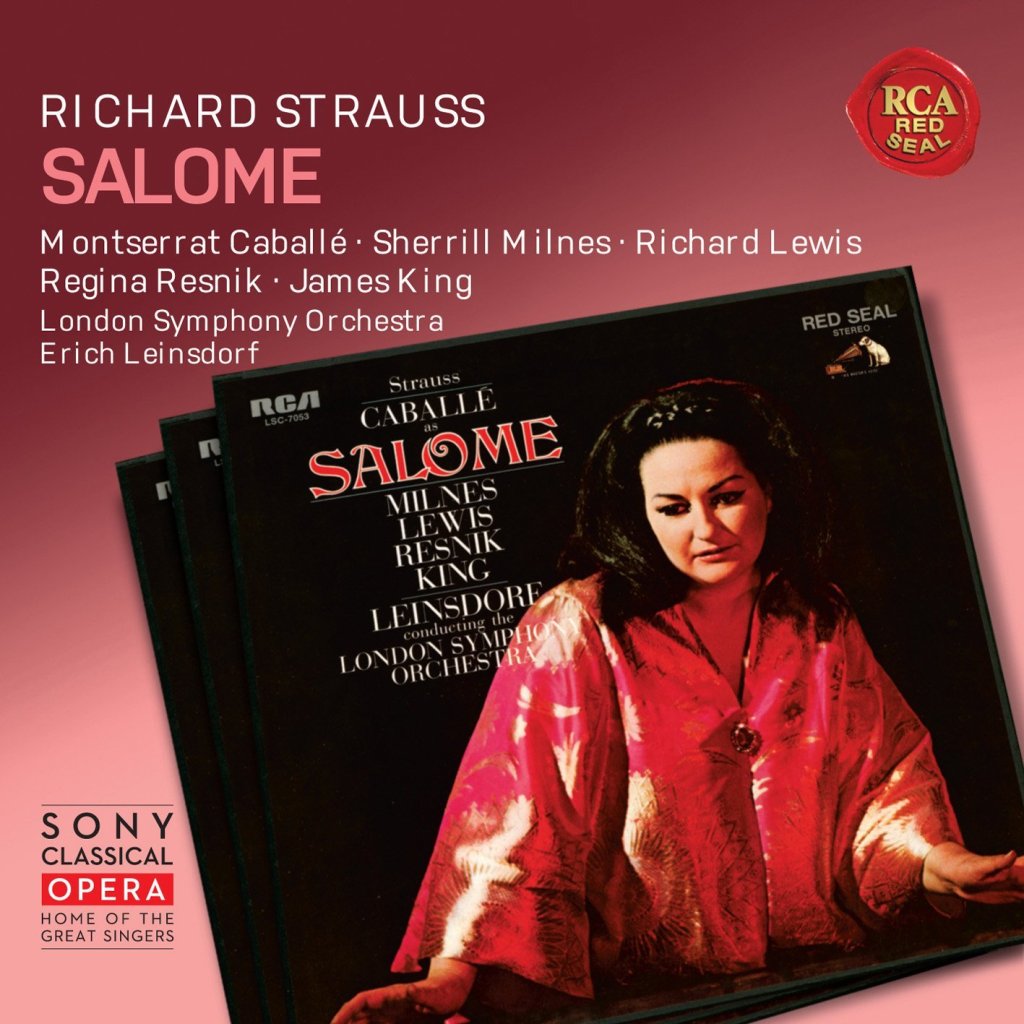

MONTSERRAT CABALLE (1969)

Montserrat Caballé? Really? Yes, really. Caballé sang her first Salome in Basel in 1957, when she was only 23 years

Salome was also the first role she sang in Vienna in 1958, and I can assure you that she was one of the very best Salomes ever. Certainly on the recording she made in 1969 under the thrilling baton of Erich Leinsdorf. Her beautiful voice, with its whisper-soft pianissimi and velvety high notes, sounded not only childlike but also very deliberately sexually charged, like a true Lolita.

Sherrill Milnes’s very charismatic Jochanaan has the aura of a fanatical cult leader, and Richard Lewis (Herod) and Regina Resnik (Herodias) complete the excellent cast

(Sony 88697579

Caballé as Salome in 1979:

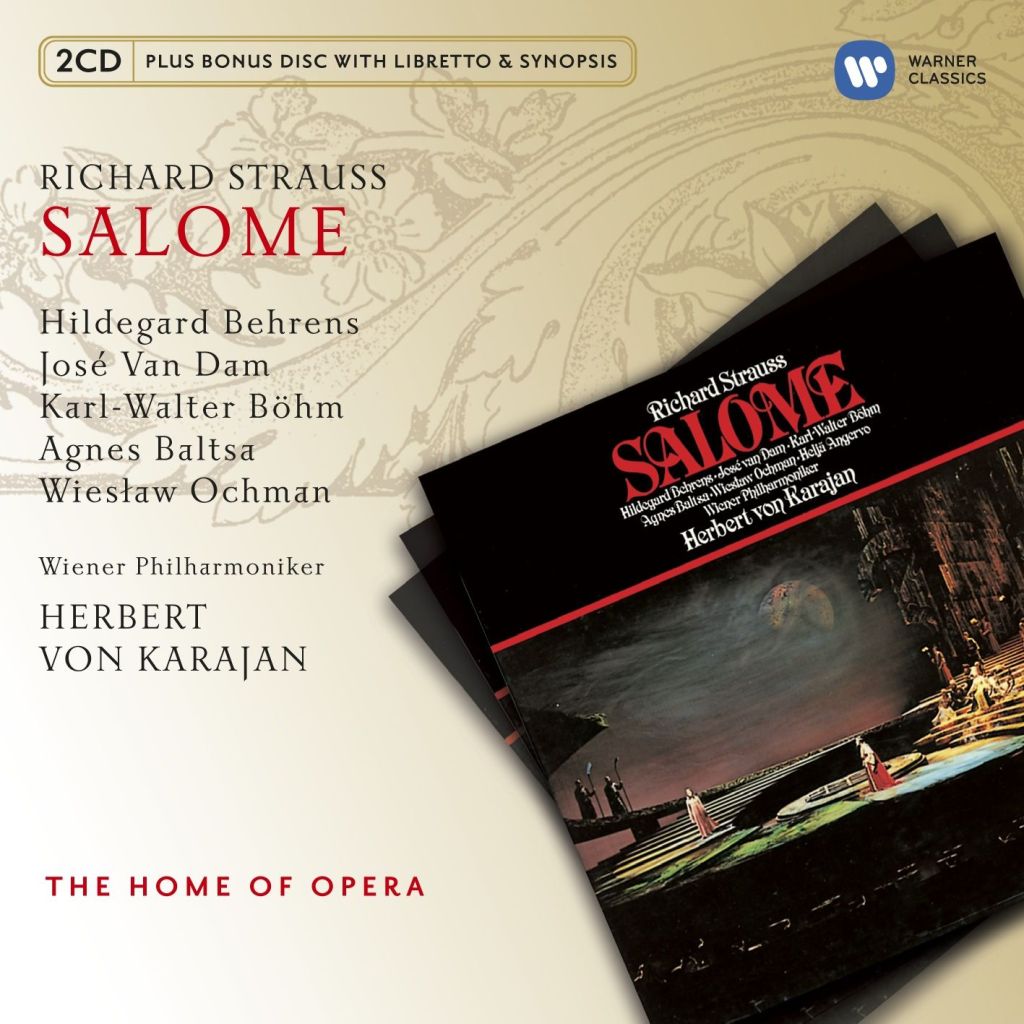

HILDEGARD BEHRENS (1978)

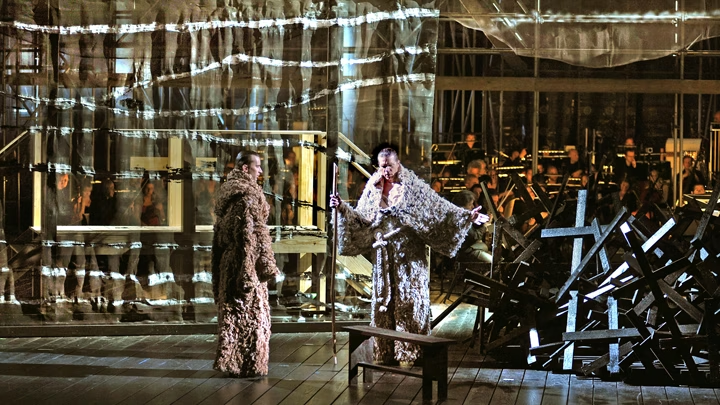

This recording is worth buying mainly because of Narraboth. Wieslaw Ochman sounds so madly in love and so terribly desperate that you really feel sorry for him. Agnes Baltsa’s Herodias is also wonderful: her interpretation of the role is one of the best I know. José van Dam is a very authoritarian Jochanaan: a true preacher and missionary, with very little appeal.

I find Hildegard Behrens’ Salome not very erotic. With her then still slightly lyrical voice, she sounds more like a spoilt child who gets angry when she doesn’t get her way. There is something to be said for his, especially since Behrens is an incredibly good voice actress and

everything she sings can be followed literally. You don’t need a libretto here.

But the real eroticism can be found in the orchestra pit: Herbert von Karajan conducts very sensually

(Warner Classics 50999 9668322).

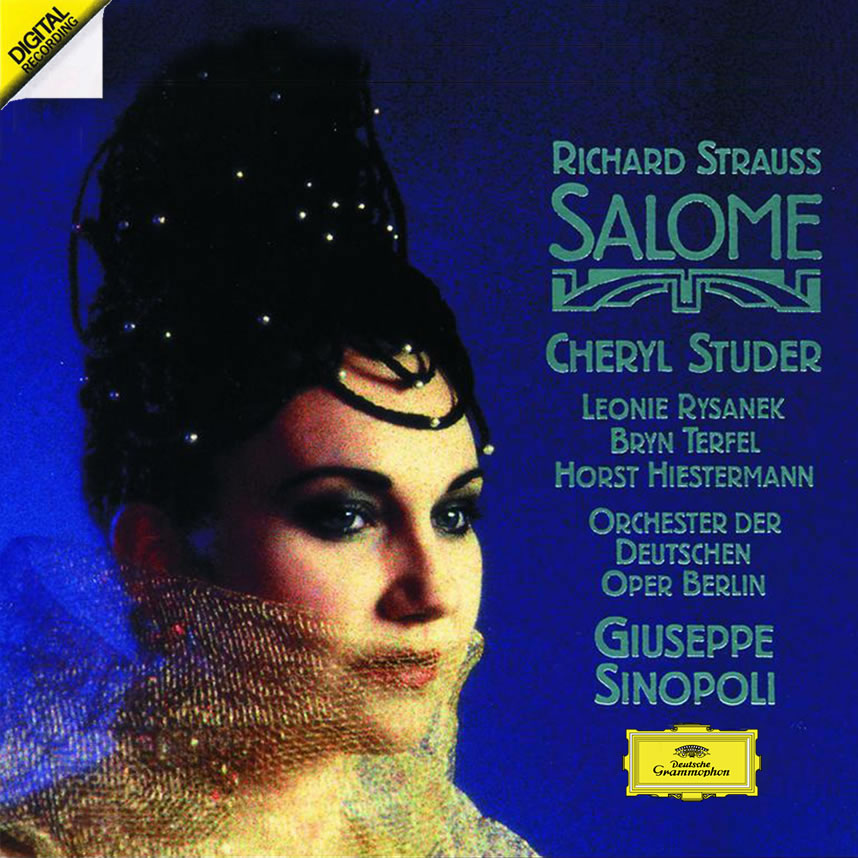

CHERYL STUDER (1991)

I realise that many of you will disagree with me, but for me Cheryl Studer is the very best Salome of the last fifty years. At least on CD, because she never sang the role in its entirety on stage

(DG 4318102).

Like few others, she knows how to portray the complex character of alome’s psyche. Just listen to her question “Von wer spricht er?”, after which she realises that the prophet is talking about hermother and sings in a surprised, childishly naive way: “Er spricht von meiner Mutter”. Masterful.

Bryn Terfel is a very virile, young Jochanaan (I think it was the first time he sang the role), but the most beautiful thing is Giuseppe Sinopoli erotic connductING

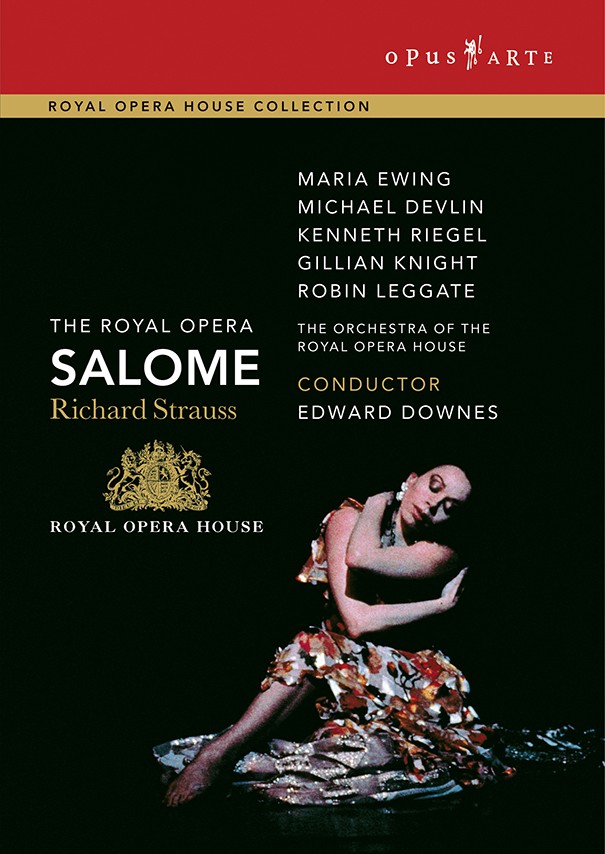

MARIA EWING (1992)

Maria Ewing also is a very good Salome. She too has the looks, and with her aggrieved expression, pouting mouth and wide-open eyes, she could easily be mistaken for a teenager. And she can sing too.

Jochanaan is sung by a very attractive American baritone, Michael Devlin, dressed only in tiny briefs. I am particularly impressed by his muscles, less so by his voice. Nevertheless, the erotically charged tension between him and Salome is palpable – that’s theatre!

Kenneth Riegel is perhaps the best Herod in history. His looks are lecherous and his voice sounds lustful, but his fear of the prophet is also almost physically palpable. Breathtaking.

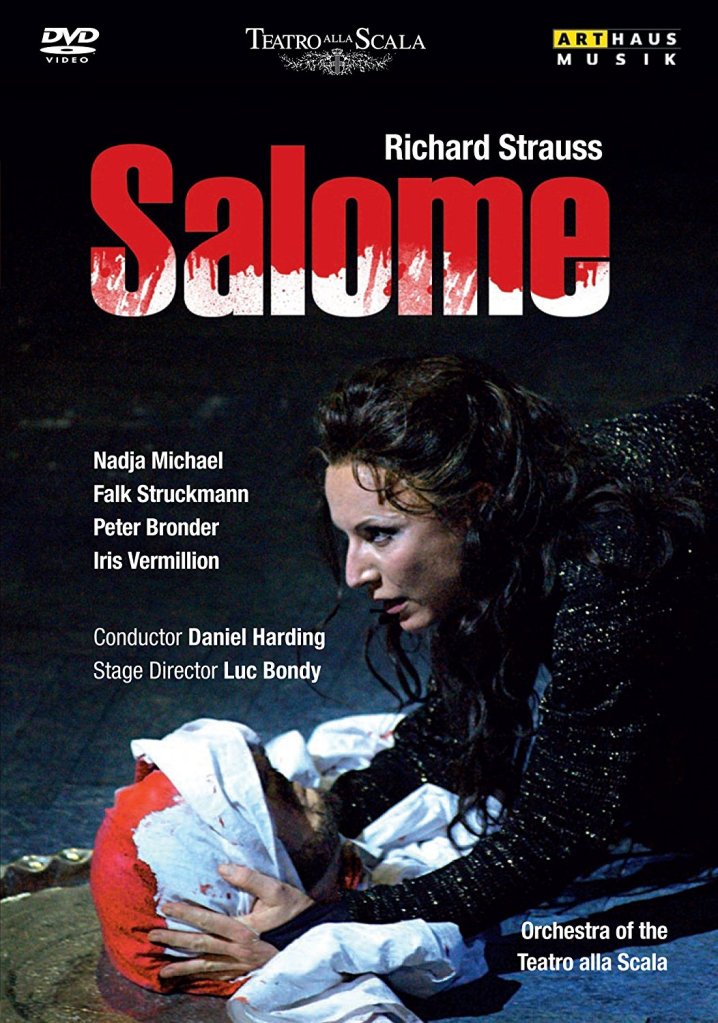

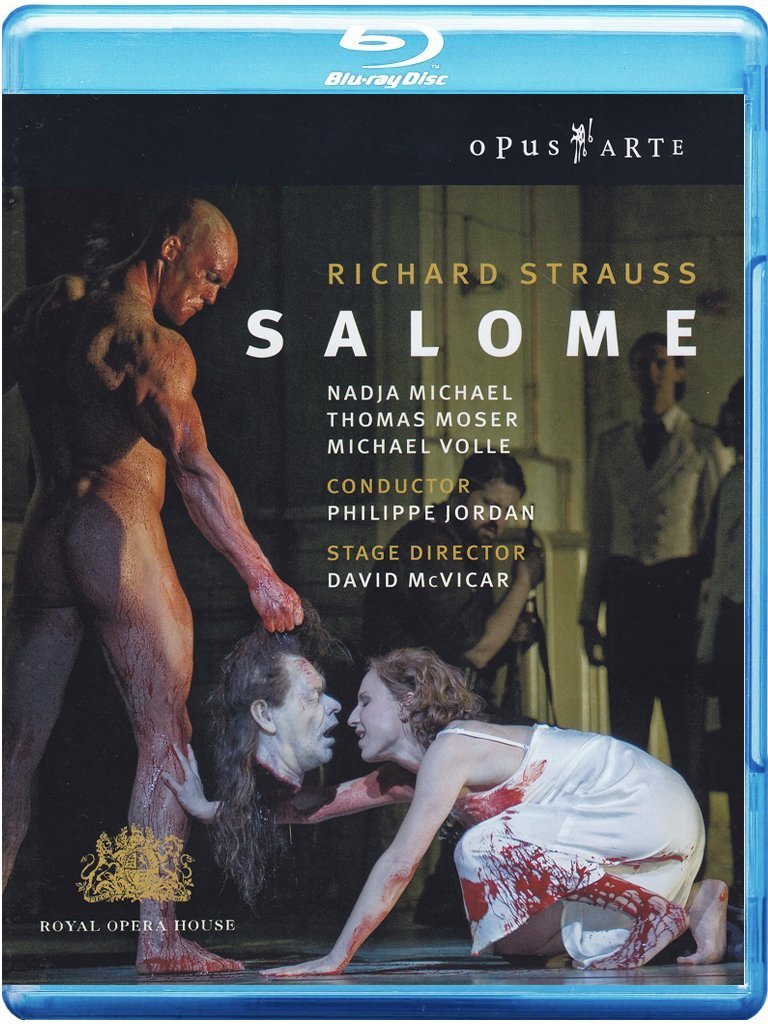

NADJA MICHAEL (2007 & 2008)

No fewer than two different DVDs starring Nadja Michael have recently been released: from La Scala (2007, directed by Luc Bondy) and from Covent Garden (2008, directed by David McVicar). Both productions are undoubtedly good, although I personally find McVicar’s version much more

exciting. good, although I personally find McVicar’s version much more exciting.

Luc Bondy’s direction (Arthaus Musc 107323) is rather traditional and actually very simple. His setting is minimalist, the colours dark, but the light shining in from the ever-present moon is simply beautiful. Iris Vermillion is a very attractive Herodias, both vocally and visually, and Herod

(a truly excellent Peter Bronder) is portrayed as a really small and miserable little man. Falk Struckmann (Jochanaan) certainly impresses with his voice, but looks too old and too sluggish.

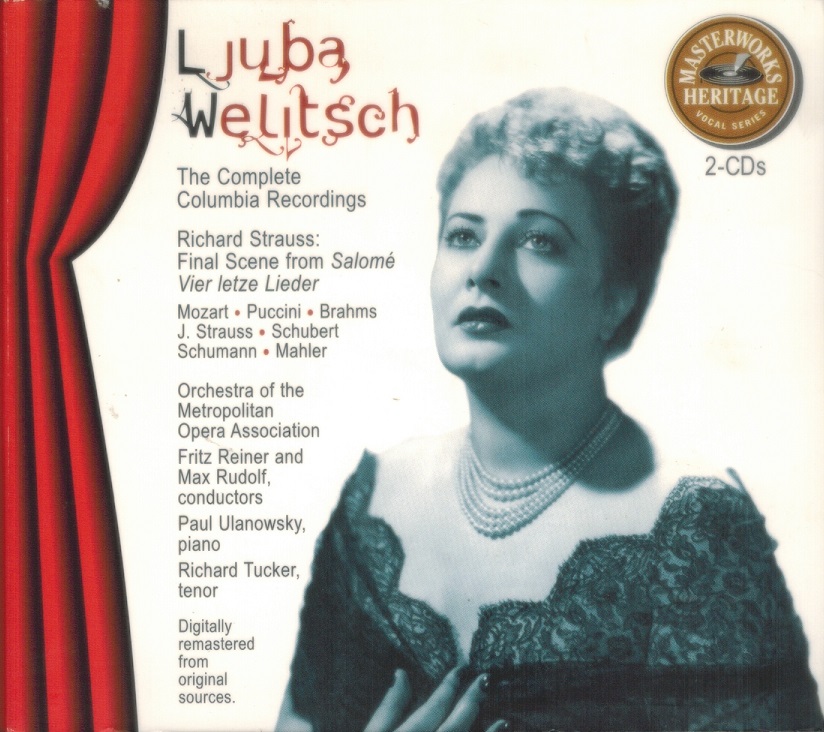

Ljuba Welitch (1949)

Whichever Salome you choose, there is one you absolutely cannot ignore:

Ljuba Welitsch. The recording she made in 1949 under Fritz Reiner,

immediately after her sensational debut at the MET in the role (Sony MHK

262866), has never been equal

On YouTube, you can also hear Welitsch in the final scene of the opera

in the 1944 recording under Lovro von Matacic