Tekst: Neil van der Linden

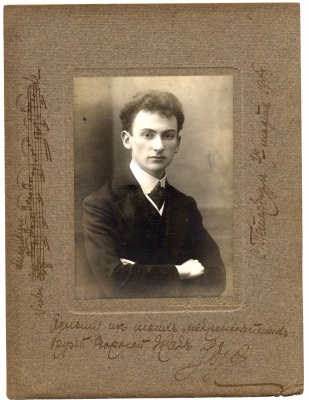

Shostakovich after the 1961 première of the Fourth Symphony at the Moscow Conservatory

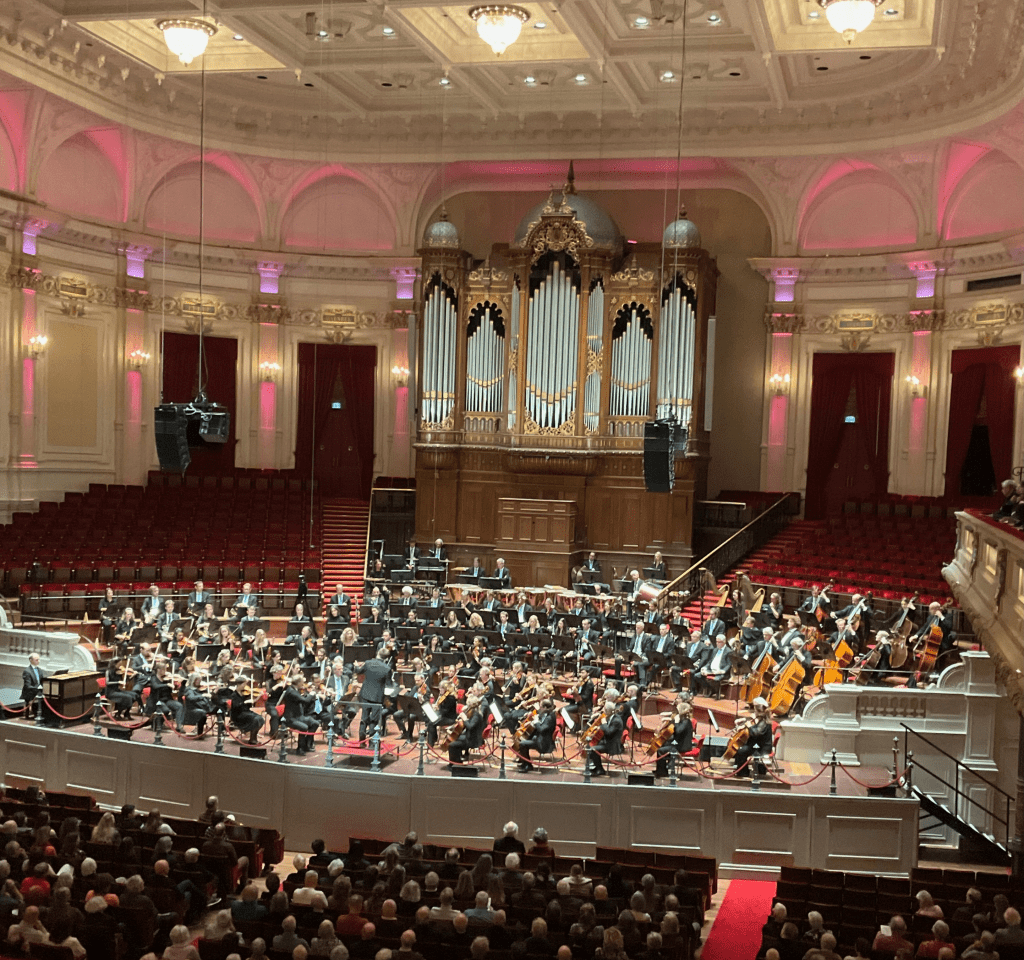

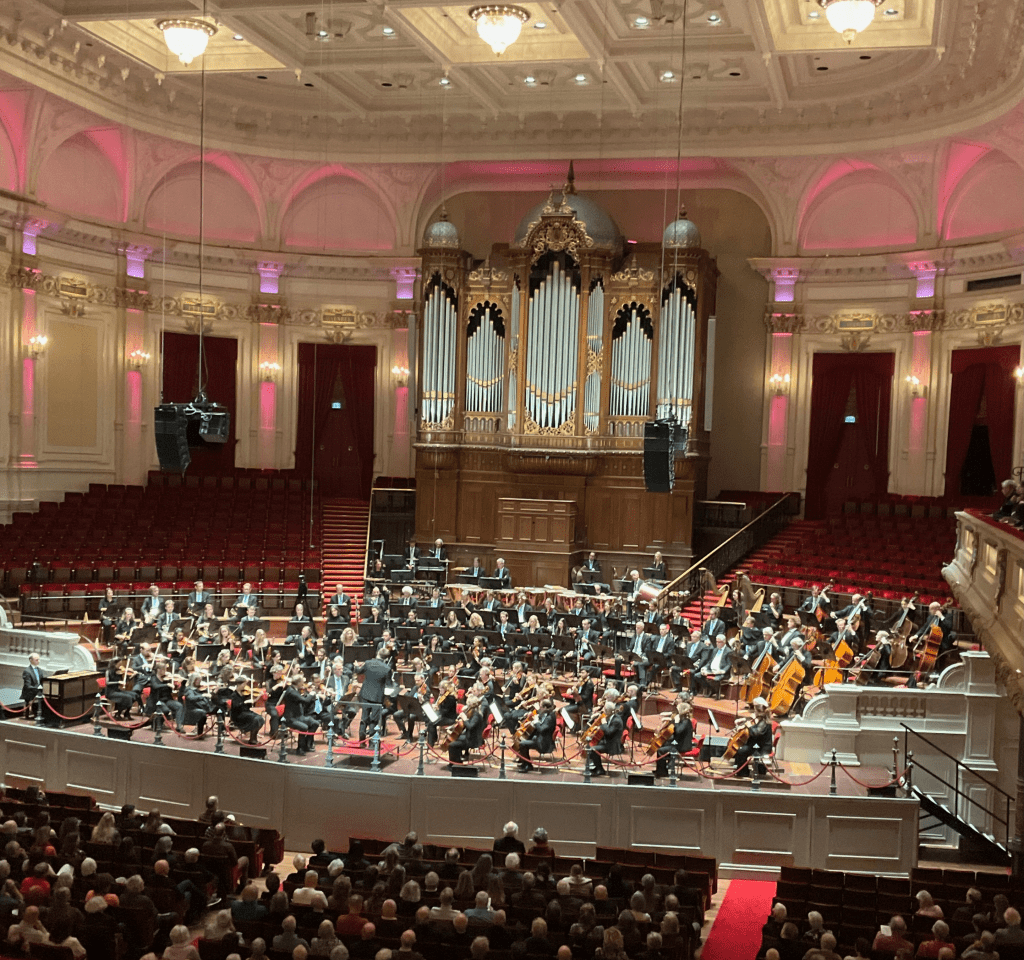

Zo’n 110 musici op het podium voor Sjostakovitsj’ Vierde symfonie. De website van de matinee heeft het over “grootheidswaanzin”, een betiteling die Sjostakovitsj zelf gebruikte voor dit werk.

Zo’n 110 musici op het podium voor Sjostakovitsj’ Vierde symfonie. De website van de matinee heeft het over “grootheidswaanzin”, een betiteling die Sjostakovitsj zelf gebruikte voor dit werk.

Het werk heeft een geschiedenis in de Zaterdag Matinee. Naast mij zat een mevrouw die het werk al rond 1980 had gehoord, onder (de toen piepjonge) Gergiev. Ook met het Radio Filharmonisch Orkest. Deze symfonie werd toen gecombineerd met Sjostakovitsj’ eerste vioolconcert, met Vladimir Repin als solist. Toen was nog iets duidelijker wat en wie goed en fout waren. Sjostakovitsj was goed en Gergiev en Repin dus ook.

Het was toen niet eens zo lang geleden dat deze symfonie eindelijk in première ging, in 1961, onder Kirill Kondrasjin. Sjostakovitsj had het werk vlak voor de première in 1936 teruggetrokken na een vernietigend artikel in de Pravda. Was de opmerking van Sjostakovitsj dat het werk ‘bol stond van grootheidswaanzin’ een soort boetedoening tegenover het Stalin-regime? Of vond hij echt dat dit werk buitenproportioneel was? Toch werkte hij door aan deze symfonie, en het Leningrads Filharmonisch Orkest zou het in première brengen, tot het orkest er op het laatste moment voor terugdeinsde. Overigens betoonde Otto Klemperer (in die jaren beslist een voorvechter van de avant-garde) zich enthousiast over het werk toen hij een pianoversie van de partituur hoorde.

De kaartenbak met extra musici van het Radio Filharmonisch Orkest is in elk geval groot genoeg om het werk te kunnen bezetten.

Maar eerst over de twee andere onderdelen van het concert.

Als eersten verschenen slechts vier musici op het podium, de leden van het Dudok Kwartet, voor het deel Strange Oscillations uit het vierde strijkkwartet van Joey Roukens, What Remains, uit 2019.De vier musici hadd en absoluut geen neiging om in de Grote Zaal te verdrinken.

Diezelfde avond draaide Aad van Nieuwenhuizen in Vrije Geluiden op NPOklassiek ook door het Dudok Kwartet een ander deel uit dit kwartet, Motectum, de Middeleeuws-Latijnse versie van het woord motet. Wat een prachtige muziek is dit allemaal….

In het volgende programmaonderdeel trad het kwartet opnieuw aan, in John Adams’ Absolute Jest (2012), voor strijkkwartet en orkest. Het is een werk vol bekende Adams-ingrediënten. Eigenlijk vooral vintage componenten: je herkent er het Wagneriaanse en Bruckneriaanse van Harmonielehre in, en de big band-jazz Duke Ellington en Count Basie-achtige orkestraties uit bijvoorbeeld The Chairman Dances. Verder voegde hij een groot aantal Beethoven-citaten toe, met name uit de Negende Symfonie en late strijkkwartetten, en ook uit de Mondschein sonate; dus wordt het dan een beetje een De Slimste Mens quiz.

Het sterkst is de componist als hij eigen elementen gebruikt, een mooie melodische lijn in de hoorns, een paar Harmonielehre-atmosferen en puntige dialogen tussen strijkkwartet en orkest. Vasily Petrenko leidde het allemaal zuiver en precies. Het was misschien voor hem ook een interessante uitdaging, want ik weet niet helemaal zeker of dit echt zijn muziek is.

Wat wel zijn muziek is bleek na de pauze in de Sjostakovitsj symfonie. Petrenko begon er meteen vol overgave aan, nu wel overtuigd van zichzelf, alsof hij een dubbele espresso op had. Nou is het begin van deze symfonie ook wel erg energiek. Het orkest volgt hem strak, spatgelijk en zuiver. Maar ook zo soepel en speels als kan binnen zo’n immense partituur, beslist een verdienste van Petrenko.

Hier klinkt duidelijk ook de jarenlange ervaring van het orkest zelf in veelzijdig grootschalig werk door, verdienste van jarenlang werken met chef-dirigenten De Waart en Van Zweden met onder meer hun Wagners en Mahlers, James Gaffigan met zijn prachtige Prokofjevs en vervolgens Canellakis in Bruckner, Janáček en Wagner .

Petrenko heeft met dit orkest eerder ook Prokofjev en Sjostakovitsj gedaan, en Rachmaninov en Rimski-Korsakovs Gouden Haan. Extra bewonderenswaardig is dat dit alles lukt in een formule waarin er meestal maar één uitvoering is, die op zaterdag in de matinee, terwijl eigenlijk altijd alles meteen raak is

Af en toe zou ik gewild hebben dat hij tussendoor nog een espressootje meer had genomen. Het energieniveau van het begin werd niet steeds volgehouden. Dat ligt een beetje ook aan de partituur, die soms wat indut. Maar al snel herpakte Petronko zich telkens. De zachte passages kneedde hij kleurrijk, ook geholpen door de muzikaliteit van de vele individuele instrumentalisten van het orkest. Sjostakovitsj maakt veelvuldig gebruik van bijzondere effecten met kwinkelerende of snerpende piccolo’s, een melodieuze althobo, diepe houtblazer tonen uit fagot en smakelijke partijen voor de basklarinet.

Petrenko gaf ze alle ruimte. Natuurlijk is het ook lekker uitpakken met de acht hoorns en het overige koper. En als dan de twee paukenisten en zeven personen divers slagwerk er ook nog tegenaan gingen (ik zag een hoboïste oordoppen indoen bij de tutti-passages) was Petrenko ook echt in zijn element. Ook in de radioregistratie van dit concert hoor je hoe alles spat zuiver en spatgelijk wordt gespeeld.

In zekere zin is deze symfonie niet eens zo afhankelijk van visie, van interpretatie, het is gewoon groot en veel. Maar dat moet dan allemaal wel goed onder controle gehouden worden. Dat gebeurde. Dat het publiek uitermate geboeid was hoor je ook in de radio-uitzending. Hoesten gebeurde voornamelijk tussen de delen in. In het eerste deel van de avond werden kwartet en orkest luid toegejuicht, na het tweede deel orkest en dirigent.

Radio Filharmonisch Orkest olv Vasily Petrenko

Dudok Quartet Amsterdam

Joey Roukens

Strange Oscillations (uit Strijkkwartet nr. 4 ‘What Remains’)

John Adams

Absolute Jest

Toegift van het kwartet: een piano-prelude van Sjostakovitsj bewerkt voor kwartet.

Dmitri Sjostakovitsj

Symfonie nr. 4 in c, op. 43

Gehoord: NTR Zaterdag Matinee, Concertgebouw, 9 november 2024

De radioregistratie:

European Union Youth Orchestra en Vasily Petrenko met Sjostakovitsj vierde:

Foto’s: © Neil van der Linden

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-8526342-1463394616-5491.jpeg.jpg)