Tekst: Neil van der Linden

In Rudi Stephans opera Die ersten Menschen zien we hoe de mens, om precies te zijn Abel, zoon van Adam en Eva, God uitvond. Religieuze thema’s waren er al te over in de opera, maar dit was nog nooit vertoond. Het operapubliek had Richard Strauss’ Salome uit 1905 al geaccepteerd, en zelfs omarmd, maar Rudi Stephans opera uit 1914 (première 1920) ging vele stappen verder.

Of die immorele strekking de belangrijkste reden is waarom de opera lange tijd werd vergeten weten we niet. De componist was in 1915 op 28-jarige leeftijd tijdens de eerste dag van zijn militaire op het slagveld van de Eerste Wereldoorlog omgekomen.

Tijdens zijn korte leven had hij een klein, verfijnd oeuvre achtergelaten. Prachtige muziek, maar moeilijk te definiëren. Tussen post-romantisch en modernistisch in. Hij was geen iconoclast als Schönberg, maar ook minder ‘conservatief’ en ‘welluidend’ dan bijvoorbeeld Korngold. Korngolds Die Tote Stadt, ook première 1920, was een enorm succes in de Duitstalige operawereld.

Eigenlijk heeft Stephans idioom wel wat weg van dat van Franz Schreker. Diens Die Gezeichneten, première 1918, was wél succesvol. Strikt genomen een niet minder immorele of amorele opera dan Die ersten Menschen, maar dan zonder de ‘Godsvraag’. Misschien hielp het ook niet dat Stephans eerdere, ook prachtige orkestwerken flegmatische titels kregen als Opus 1 für Orchester, Musik für sieben Saiteninstrumente, Musik für Orchester, Musik für Geige und Orchester.

De opera, naar een libretto van Otto Borngräber, gaat over Adahm, Chawa, Kajin en Chabel, de Hebreeuwse namen voor Adam, Eva, Kain en Abel. Het is dus een familiedrama. Maar dan wel heel Freudiaans; de theorieën van de psychoanalyse waren net in zwang gekomen. Adahm is bezig met zijn werk (in de voorstelling zit hij een groot deel van de tijd achter een laptop), en heeft geen tijd voor dan wel geen zin in Chawa’s behoefte aan huiselijkheid en haar seksuele verlangens.

Kajin, de oudste zoon, wordt afgewezen door vooral zijn vader maar ook door zijn moeder. Hij trekt eropuit, de wilde wereld in, op zoek naar ‘Das Wilde Weib’; dat er strikt volgens de Bijbel maar vier mensen waren op de wereld – Die ersten Menschen – doet er even niet toe. Maar hij komt erachter dat zijn moeder eigenlijk de ideale vrouw is. Hij keert terug, maar als zij hem negeert, randt hij haar min of meer aan. Maar ze geeft toe, omdat ze in een fantasie denkt dat het Adahm is. Als ze bij zinnen komt, schudt ze hem van zich af. Chawa valt dan weer wel op haar andere zoon Chabel, de Benjamin van de hele familie. Vervolgens ontpopt Chabel zich tot profeet, en vindt God uit; de mens schept God naar zijn evenbeeld, aldus de tekst. Chawa en Adahm bekeren zich onmiddellijk enthousiast tot de nieuwe leer.

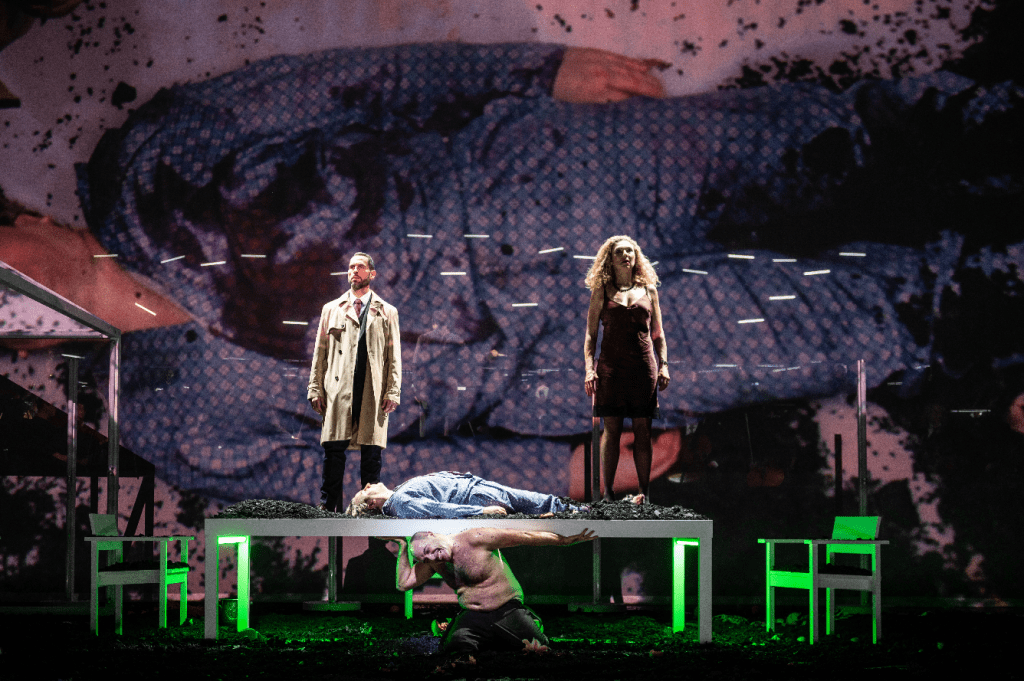

De handeling speelt zich op en rond een enorme witte tafel af. In de openingsscène is het een eettafel bezaait met vruchten. Later wordt een offertafel, de plek waar de protagonisten seks hebben, een schuilplaats voor Kajin, het kruisbeeld en volgens mij zelfs de wereld. Hierover verderop meer.

De rolbezetting is dezelfde als bij de première van de voorstelling drie jaar geleden, en die was en is ijzersterk. Sopraan Annette Dasch is een fenomenale Chawa en trekt daarbij wel alle registers open, zowel vocaal- als acteer-technisch

Als je Chawa’s karaktertekening in het libretto als misogyn wil zien, dan verandert Bieito daar weinig aan. Ze moet de hele tijd verleidelijk zijn, ze loopt heupwiegend rond, komt met de ene na de andere sensuele jurk opkomen, enz. Maar dat doet Dasch overtuigend.

Adahm (bas-bariton Kyle Ketelsen) zet fraai een wijfelaar neer, die een al wat bezadigder levenshouding heeft. Zijn respectievelijke “Chabel, mein Sohn” en “Kajin, mein Sohn” laat hij net zo gebiedend klinken als Alberichs “Hagen, mein Sohn” in Wagners Götterdämmerung moet zijn, en ik denk dat Stephan in deze korte frasen Wagner muzikaal letterlijk citeert.

De eveneens fraai zingende bariton Leigh Melrose (Kajin) drukt zowel de wanhoop als het machismo uit die in de rol zitten. Zijn personage wekt ook empathie, ondanks de broedermoord. Nou ja, die moest gebeuren. En bovendien is Chabel eigenlijk een ontzettende druiloor, een grote baby, uit een horrorfilm. John Osborn zet hem geweldig neer. De rol schrijft hele passages in falsetregisters voor. Die geven Chabel iets onaards, maar in deze enscenering maakt John Osborn er een bijna-gek van, een Parsifaleske reine Tor, een associatie die past bij de Parsifaliaanse muziek die Stephan hem meegeeft als hij zijn visioenen profeteert.

Chabel brengt een lam mee naar huis, het Lam Gods. Maar het is een onooglijke vuilwit-pluchen speelgoedbeest. Als een verwend kind snijdt Chabel het beest aan stukken. “Het offer” noemt Chabel het. Het eerste offer, volgens het libretto, het tweede offer wordt Chabel even later zelf, wanneer hij, Bijbel-conform, door Kajin wordt vermoord. De Jezus-analogie ligt er duimendik bovenop, en Bieito buit die gretig uit. Chabels ‘kindsheid’ belet Bieito overigens niet om voorafgaand aan de broedermoord een prachtig in scène gezette seksscène te hebben, met Chawa, maar intussen ook met Kajin, en met alle twee tegelijk.

Uiteindelijk vinden Chawa en Adahm elkaar weer, en we zien hen tegenover een ‘sterrennacht’ (lampjes boven het orkest) zingen dat de toekomst er toch hoopvol uit ziet en dat ze ervoor gaan zorgen dat er nog een zoon zal komen. (Dat zou volgens de Bijbel dan Seth moeten worden, de ‘vergeten’ derde zoon van Adam en Eva.)

Kleuren en uitlichting, ook van alle bloemen en vruchten die door het decor slingeren, doen denken aan Caravaggio. Chawa zingt dat ze van bloemen houdt terwijl Adahm stelt dat voor hem de vruchten het belangrijkst zijn; Chawa smijt daarop lustig kilo’s meloenen, sinaasappels en ananassen kapot.

Ook de mystiek-erotische tekst roept associaties met Caravaggio op. Bijvoorbeeld zijn in zijn Conversione di San Paolo zien we Saulus c.q. Paulus, als hij op weg naar Damascus, verblind door Goddelijk licht, zo te zien een bijna orgastische ervaring beleeft.

Het orkest zit net als drie jaar geleden weer op het podium. Dat was toen vanwege Corona. Zo kon je met minder musici toch een mooie orkestklank krijgen. De opstelling van toen is gehandhaafd, maar nu was het mogelijk met voltallig orkest te werken. Het Rotterdams Philharmonisch Orkest klinkt op deze manier spectaculair. Dirigent Kwamé Ryan weet intussen ondanks het veel grotere orkest een fraai klinkende balans met de zangers te bereiken.

Het orkest heeft trouwens een rol in het decor. Als de protagonisten het aan het begin en aan het eind over de sterren hebben lichten de lampen boven het orkest zachtjes op. Tussen orkest en speelvloer hangt het grootste deel van de tijd een gaasdoek, maar als de personages ergens tijdens de tekst vertellen dat ze de waarheid zien of zoiets dan gaat het gaasdoek omhoog; om even later als hun blik blijkbaar weer vertroebelt omlaag te gaan.

Als Kajin uiteindelijk als een verschrompeld hoopje ellende onder de tafel ligt, lijkt hij even op Judas. Heb ik nou ergens ooit gelezen dat Judas misschien een broer van Jezus was? Maar helemaal tegen het eind spreidt hij zijn armen uit langs het tafelblad. Een verwijzing naar Jezus zelf? En dan moet ik ook even denken aan Atlas uit de Griekse mythologie, die de wereld op zijn schouders draagt.

Bieito zou toen eigenlijk Berlioz’ La Damnation de Faust regisseren. Om Corona-redenen moest die plaats maken voor een werk met veel minder personages. Ik hoop dat we die Damnation nog tegoed hebben.

Rudi Stephan (1887 – 1915) Die ersten Menschen (1914, première 1920)

Libretto Otto Borngräber

Regie Calixto Bieito

Adahm Kyle Ketelsen

Chawa Annette Dasch

Kajin Leigh Melrose

Chabel John Osborn

Decor Rebecca Ringst

Rotterdams Philharmonisch Orkest

Muzikale leiding Kwamé Ryan

Foto’s © Bart Grietens

Trailers van de productie van drie jaar geleden:

Op CD via Spotify :

.

Over Seth, Adam en Eva’s derde zoon:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seth

Over Die Gezeichneten van Schreker:

https://basiaconfuoco.com/2017/01/21/die-gezeichneten-discografie/