Tekst: Neil van der Linden

Je ziet een voormalig hoofd van de (Britse inlichtingendienst de) M15 verklaren dat de beste methode om je wil door te drijven is om partijen te vinden die je tegen elkaar kunt opzetten.

Je ziet Eisenhower glashard bij de Verenigde Naties verklaren dat de soevereiniteit van nieuwe landen heilig is en dat buitenlandse inmenging uit den boze is. Even later een hoofd van de CIA aan het woord komt die vertelt dat Eisenhower had gezegd dat Patrice Lumumba, de nieuw gekozen president van het net onafhankelijk geworden Congo, aan de krokodillen moest worden gevoerd. En dat hij als lid van de delegatie die met Louis Armstrong meereisde een pistool mee kreeg waarmee je een onzichtbaar ijspijltje kon afschieten dat zonder dat het beoogde het slachtoffer het zelfs maar zou voelen een gif zou inspuiten dat een hartaanval kon veroorzaken.

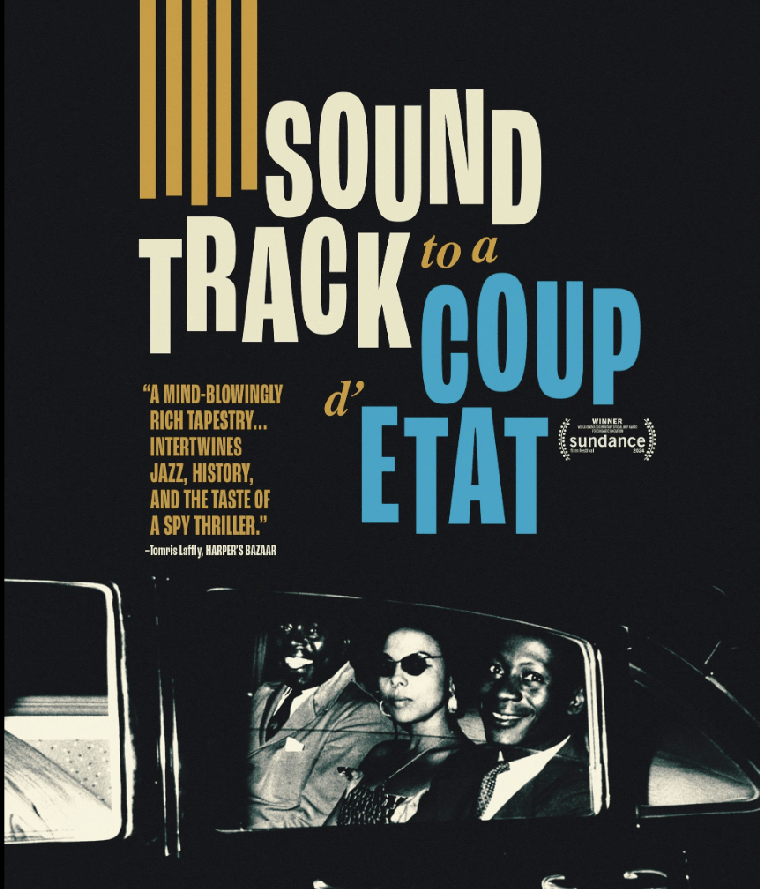

The murder of Congo’s first post-independence leader Patrice Lumumba took place as famed jazzman Louis Armstrong was touring the country. The two events were not a coincidence, as the acclaimed documentary, ‘Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat’, reveals.

https://www.brusselstimes.com/1103100/how-jazz-played-out-over-congos-chaotic-coup

Je ziet even later Louis Armstrong verklaren dat hij daarna zijn Amerikaans burgerschap wil opgeven en naar Ghana wil verhuizen.

Louis Armstrong and the spy: how the CIA used him as a ‘trojan horse’ in Congo

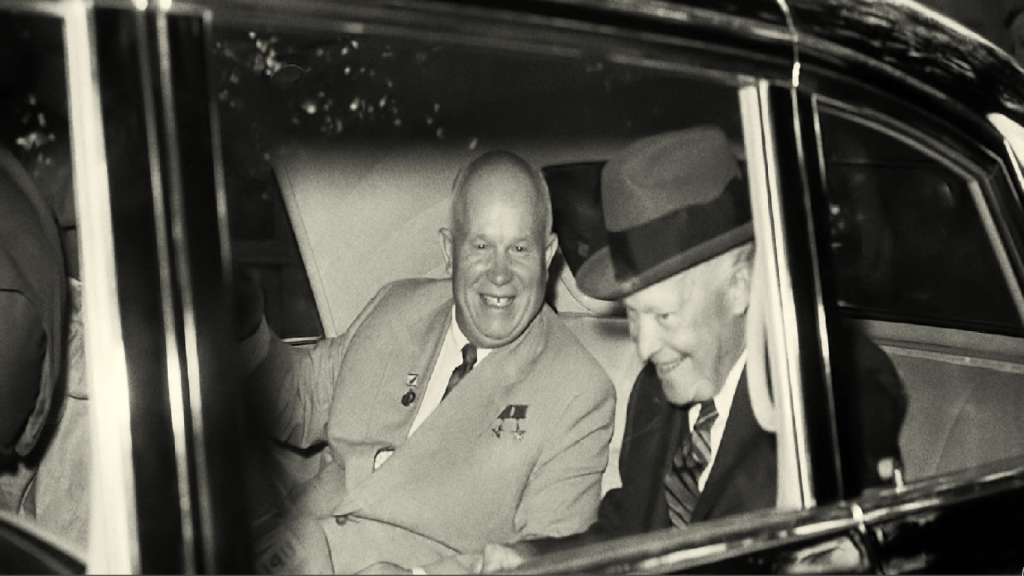

Je ziet Khruschev zich bij de VN als held van de nieuwe landen ontpoppen als hij verklaart dat buitenlandse inmenging taboe is. Je weet dat de Sovjets in 1956 een bloedig einde maakten aan de Hongaarse Opstand.

We zien de beroemde scenes waarin gedirigeerd door Khruschev de delegatie van de USSR (toen nog maar net toegelaten tot de VN; China was nog buitengesloten – ergens in de documentaire wordt gezegd dat de VN eigenlijk gewoon een instrument was van de VS) bij een aantal toespraken van Eisenhower en met name na het bericht over de dood van Lumumba met de vuisten op tafel trommelt. Of Khruschev nou werkelijk ook met een schoen op tafel had getrommeld is niet goed te zien.

Je ziet Rostropovich optreden bij de Verenigde Naties, waarna de toenmalige Secretaris General Dag Hammarskjöld verklaart dat muziek een taal is die ook kan uitdrukken wat niet onder woorden kan worden gebracht en die iedereen voelt. Cultural diplomacy vond over en weer op alle fronten plaats. Hoewel musici als Rostropovich zich later als dissident opwierpen, was het de VS een doorn in het oog dat de USSR zich meer en meer het monopolie op ‘hoogstaande’ klassieke als soft power toeëigende.

Daarop besloten de VS juist de andere kant op te gaan en als tegenwapen de ‘volksere’ jazz te gebruiken. Daarin zouden misschien bijvoorbeeld de mensen uit Afrika zich meer herkennen. Wat in een ricochet-effect had toen de Amerikaanse jazz-musici zich meer en meer met de Afrikaanse dekolonisatiebewegingen gingen identificeren en bijvoorbeeld bij monde van Malcolm X Lumumba tot held verklaarden.

Jazz Diplomacy during the Cold War | The Jazz Ambassadors

Vervolgens horen we een interviewfragment met Khruschev waarin hij verklaarde dat jazz geen muziek is. (Dat kenden we ook al van de Nazis.) De documentairemaker mixt briljant het geluid van het getrommel op tafel door de Soviet-delegatie met de slagwerkgeroffel van Max Roach en voetgeraffel van Dizzy Gillespie. Even daarvoor zagen we hoe Dizzy Gillespie zich kandidaat had gesteld voor het presidentschap van de VS, eerst als grap, maar het werd vervolgens kreeg het een serieuzere kant.

Louis Armstrong wordt warm onthaald in Ghana en treedt op voor 100000 mensen, naar wordt beweerd het grootste concertpubliek tot dan toe ooit. Ghana’s president Nkruma, één van de toonaangevende leiders in de Afrikaanse onafhankelijkheidsbeweging, krijgt tranen in de ogen als Armstrong een lied aan hem opdraagt, “Black and Blue”.

Jazz als een alternatief voor de high brow cultural diplomacy door de USSR.

Strains of Freedom Jazz Diplomacy and the Paradox of Civil Rights

Louis Armstrong, als vrolijk ogende en goedlachse persoon, die ‘niet al te moeilijke’ muziek maakt, was het “Trojaanse paard” van de Amerikaanse jazz-diplomatie, zoals onderzoekster Susan Williams het beschrijft, en we zien hem ook in Egypte. De New York Times wordt in de film geciteerd, die jazz het belangrijkste instrument in de Amerikaanse buitenlandse betrekkingen met een ‘blue’ mineur akkoord noemt.

Andere jazz musici waarvan we beelden zien zijn John Coltrane, Duke Ellington die fraai uitlegt dat hij geen jazz speelt maar op de piano droomt en die we in Iran en Syrië zien. Ornette Coleman en Art Blakey die allebei categorisch weigerden zich in te laten zetten voor de diplomatie, Nina Simone en wel verschillende keren, onder meer prachtig uit het raam van vliegtuig kijkend, op weg naar een Afrikaans land. Maar juist Simone had al vroeg in de gaten dat ze werd gebruikt en bedankte verder voor de eer.

Prachtig zijn ook de beelden van Abbey Lincoln, die van de Cubaanse VN delegatie toegangskaarten had gekregen voor de VN-vergadering na de moord op Lumumba en met zestig medestanders een luide protestactie voerde, voor ze met geweld de zaal werden uitgezet; Lincoln werd het werk daarna zo moeilijk mogelijk gemaakt. We zien haar met Max Roach in prachtig fragmenten uit ‘We Insist! Max Roach’ Freedom Now Suite’ waarin ze de schreeuw herhaalt die haar ook beroemd maakte in de vergaderzaal van de Verenigde Naties.

We Insist! Max Roach’ Freedom Now Suite’

Veel aandacht is er ook voor Dag Hammarskjöld. Als Lumumba als nog steeds wettelijk gekozen president van Congo, tijdens zijn door legerkolonel Mobutu op instigatie van de VS en met medewerking van de VN ingestelde huisarrest, Hammarskjöld vraagt om bij de VN te mogen komen spreken, zegt Hammarskjöld ja maar weigert intussen op last van de VS een vliegtuig te sturen. Bovendien wordt het inreisvisum voor Lumumba door de VS geweigerd. Even later vindt de moord op Lumumba plaats.

Dag Hammarskjöld: “I shall remain in my post!” (1960), nadat zijn positie wankelde toen zijn bedenkelijke rol bij de moord op Lumumba duidelijk werd. Schrijnend is ook hoe een aantal landen daarop het aftreden van Hammarskjöld eist, maar hij zich er, met instemming van het Westen, ‘pre-Ruttiaans’ (zoals Rutte) uitkletst. Zie zijn toespraak in de Youtube link.

De rol van professionele huurmoordenaars komt ter sprake. Uit Zuid-Afrika, België en Duitsland bijvoorbeeld. Een Duitse huurmoordenaar verklaart hoe hij een goed leven had: mooi weer, af en toe schieten en een bankrekening thuis die dagelijks werd bijgevuld. Intussen is hij echt een beschaafde persoon, wil hij de interviewer laten weten, want tijdens rustperioden in de hoofdstad Leopoldville (het tegenwoordige Kinshasa) gaat hij ook naar de concerten met klassieke muziek die het plaatselijke Goethe Instituut organiseert.

De documentaire is een oogverblindend en bijna oorverdovend inferno van met elkaar verweven verhaallijnen. Voor wie de Congo-crisis indertijd via het wereldnieuws heeft meegemaakt is deze documentaire ook een soundtrack bij herinneringen aan namen die dagelijks door het nieuws gonsden.

Lumumba, Kasa Vubu, Tshombe, Mobutu, Katanga (de Congolese provincie in het zuidwesten waar – en daar ging het allemaal om – de uraniummijnen lagen waarvan het atoomprogramma van het Westen afhankelijk was. De bommen op Nagasaki en Hiroshima waren met uranium uit Katanga vervaardigd. In Katanga liggen ook belangrijke koper-, diamant- en cobalt-mijnen. De laatsten spelen nu net zo’n verderfelijke rol als toen vanwege de wereldvraag naar grondstoffen voor de batterijen voor onze Tesla’s en iPhones.

De uraniumtoevoer was tot de Congolese onafhankelijkheid in handen van het Belgische staatsbedrijf Union Minière, maar twee dagen voor onafhankelijkheid werd de Union Minière (nog zo’n naam uit het wereldnieuws-geluidsdecor van toen) geprivatiseerd en werden de Belgische staat en de Belgische koning aandeelhouders. Zo bleef het bedrijf uit handen van de Congolese staat. Bovendien steunden België en VS de afscheiding van Katanga en kwam daar een marionet aan de macht, Tshombe.

Het geheel wordt nog duizelingwekkender als je je realiseert dat de gebeurtenissen tussen de onafhankelijkheid van Congo en de moord op Lumumba zich in een periode van nauwelijks zes maanden hebben afgespeeld. Na dit bloedige half jaar was de toevoer van uranium uit de mijnen van Katanga weer veiliggesteld.

Dit alles dus in een spectaculaire montage, ‘a syncopated thriller’ zegt de trailer. In de esthetiek van televisie uit de jaren vijftig gemengd met het design van de klassieke Blue Note LP-hoezen. Schrijnend zijn dan de fragmenten van Congolese zangers zoals Franco die tijdens het huisarrest van en na de moord op Lumumba vragen om zijn terugkeer.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat – Official Trailer

Balla Et Ses Balladins – Lumumba

Lumumba – Salum Abdala & Kiko Kids

Mariam Makeba Lumumba

En dit is toch hartverscheurend, inclusief een pleidooi voor een grondig onderzoek

Lumumba, Héros National – Franco & L’O.K. Jazz 1967