“This is my best opera,” Giuseppe Verdi said after the premiere. And added that he “could probably never write anything so beautiful again”. That the “never” wasn’t completely correct, we know now, but at the time, some kind of electric shock must really have gone through the audience. Even now, more than 170 years after its premiere, Rigoletto continues to top the opera charts, as ever. I therefore sincerely wonder if there are any opera lovers left who do not have at least one recording of the ‘Verdi cracker’ on their shelves.

Design by Giuseppe Bertoja for the world premiere of Rigoletto (second scene of the first act)

Ettore Bastianini

My all-time favourite is a 1960 Ricordi recording (now Sony 74321 68779 2), starring an absolutely unmatchable Ettore Bastianini. His Rigoletto is so warm and human, and so full of pent-up frustrations, that his call for “vendetta” is only natural.

Renata Scotto sings a girlishly naïve Gilda, who is transformed into a mature woman by her love for the wrong man. She understands like no other, that the whole business of revenge can lead nowhere and sacrifices herself, to stop all this bloodshed and hatred.

Alfredo Kraus is a Duca in a thousand: elegant and aloof, courteous, yet cold as ice. Not so much mean, but totally disinterested and therefore all the more dangerous.

A sonorous Yvo Vinco (Sparafucile) and deliciously vulgar seductive Fiorenza Cossotto (Maddalena) are not to be sneezed at either, and the whole thing is under the inspired direction of Gianandrea Gavazzeni. Unfortunately, the sound is not too good, but a true fan will take it for granted.

Bastianini and Scotto in the finale:

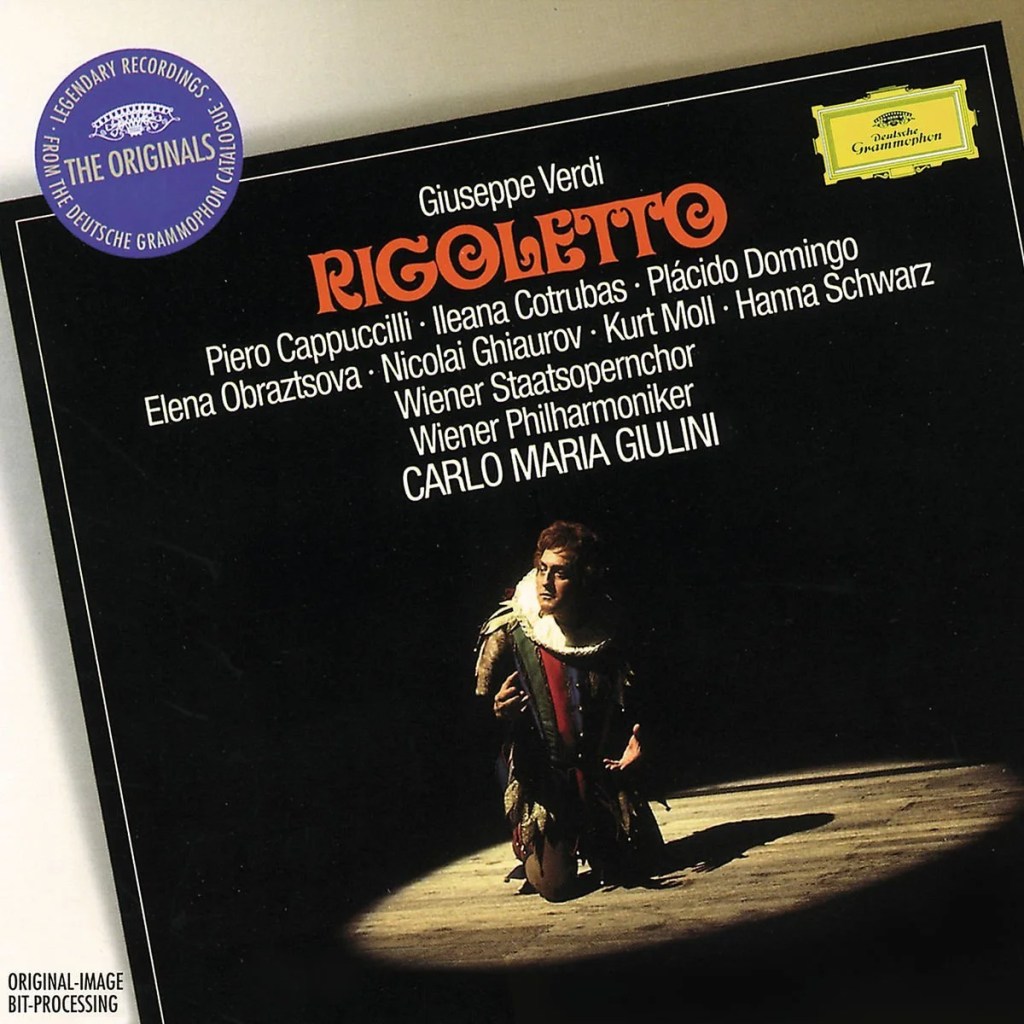

Piero Cappuccilli

My other great favourite is the performance recorded in 1980 under Carlo Maria Giulini (DG 457 7532). Ileana Cotrubas is Gilda incarnate. She is not quite a vocal acrobat à la Gruberova, nor a wagging ‘canary’ like Lina Palliughi, decidedly less dramatic than Callas (rightly so, a Gilda is not a Leonora) and perhaps not as brilliant as Sutherland, but what empathy! What commitment! What an understanding of the text! Her Gilda, unlike Scotto’s, never grows old, and her sacrifice is a teenage girls’ own: senseless and pointless and so all the more moving.

The Duca is sung by Plácido Domingo, not really my favourite for the role, though there is nothing at all wrong with his singing. Piero Cappuccilli is a truly phenomenal Rigoletto, they don’t make ‘em like that anymore.

But we shouldn’t forget Giulini, because so lovingly as he handles the score that it couldn’t be more beautiful.

Tito Gobbi

The 1955 recording with Maria Callas (Warner Classics 0825646340958) conducted by Tulio Serafin sounds pretty dull. Giuseppe Di Stefano is a pretty much perfect Duca: seductive macho, suave and totally unreliable. That his high notes in ‘Questa o Quella’ come out a bit squeezed, well… for this, he is forgiven.

Tito Gobbi is simply inimitable. Where else can you find a baritone with so many expressions at his disposal? This is no longer singing this is a lesson in acting with your voice! What you should also have the recording for is Nicola Zaccaria as Sparafucile. Unforgettable.

And Callas? Hmm. Too mature, too dramatic, too present.

Gobbi and Callas sing ‘Si, vendetta! Tremenda vendetta’

Sherrill Milnes

Joan Sutherland is a different story. Light voice, sparkling and indescribably virtuosic but a silly teenager? No.

Luciano Pavarotti is, I think, one of the best and most ideal Ducas in history. There is something appealingly vulgar in his voice that makes him sexually desirable which easily explains his several conquests.

Sherrill Milnes is a touching jester, who never wants to become a real jester: no matter how well he tries, he remains a loving father.

Matteo Manuguerra

Nowadays, hardly anyone knows him, but in the 1970s, Tunisian-born Manuguerra was considered one of the greatest interpreters of both bel canto and verismo.. And Verdi, of course, because his beautiful, warm, smooth-lined voice enabled him to switch genres easily.

Anyway, of course, you listen to this pirate recording (it is also for sale as a CD) mainly because of Cristina Deutekom. Just listen how, in the quartet ‘Bella figlia dell’amore’, she goes with a breathtaking portamento to the high D from the chest register. No one imitates her in that. For that, you take Giuliano Ciannella’s screaming and understated Duca at face value. The sound is abominably bad, but then again: are you a fan or not?

DVD’S

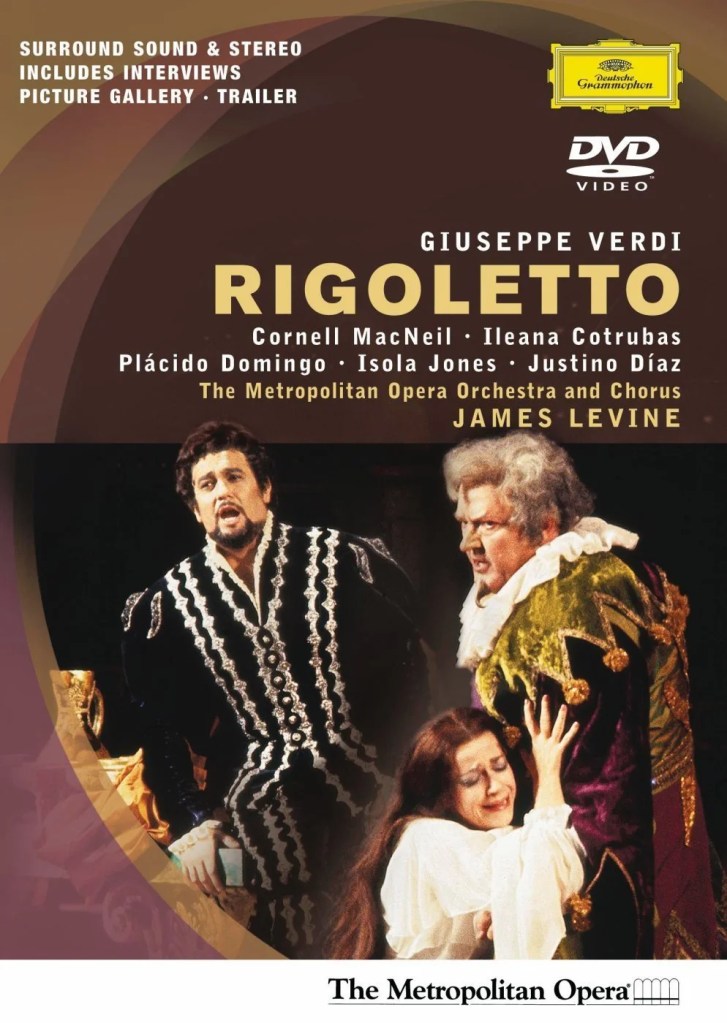

John Dexter

The 1977 production from the Metropolitan Opera (DG 0730939) is – of course – traditional. At first I had trouble with the close ups, which made all those stuck-up noses and thickly painted faces far too visible. But gradually I gave in to the beautiful direction and scenography which, together with the genuine 16th-century costumes, soon reminded me of Giorgione’s paintings. That this was indeed the intention was evident at the end, modelled on his ‘La Tempesta’, including the landscape and the sky drawn by lightning. But before it came to that, Rigoletto knelt with the dead Gilda (in blue, yes!) in his arms like Michelangelo’s “Pieta”, and I searched for a handkerchief because by now I had burst into tears.

Cornell MacNeil had his better days and started off rather false, but halfway through the first act, there was nothing wrong with his singing. And in the second act he sang just about the most impressive ‘Cortigiani’ I have ever heard, helped wonderfully by Levine’s very exciting accompaniment. Just watch how he pronounces the word ‘dannati’. Goosebumps.

It is an enormous pleasure to see and hear a young Domingo: tall, slim and handsome, and with a voice that audibly has no limitations, but…. As a Duca he goes nowhere. No matter how he tries his best – his eyes look cheerful and kind, and his lips constantly curl into a friendly smile. A “lover boy”, sure, but with no ill intentions. And he knows it himself, because he has sung that role very little. Actually, he hates Duca, at least so he says in an interview in a “bonus” to the Fragment from the second act:

Charles Roubaud

I heard a lot of good things about the performance at the arena in Verona in 2001. Reviews of the performances were rave, and people were also generally very positive about the DVD (Arthaus Musik 107096). So this will be just me, but I don’t like it.

The scenery is very sparse and looks very minimal on the large stage. It is still most reminiscent of cube boxes, but when the camera comes closer (and sometimes it comes too close!) they turn out to be walls, which close at the end in a very ingenious way – like a stage cloth, a nice invention though. The costumes are more or less okay, but I can’t find them brilliant either. And Rigoletto’s hunched back is downright ridiculous.

Leo Nucci is among the great Verdi baritones of our time but on the DVD his voice sounds anything but beautiful and in his first scenes he seems to be doing sprechgeang. Sure, his portrayal is certainly impressive, but I have seen him do better. The audience does enthuse, forcing him to encore ‘La Vendetta’ at the end of the second act.

It is not the last encore this evening: Aquiles Machado (Duca) also repeats with visible pleasure his, to my ears, roared-out ‘La donna e mobile’. It seems to be a tradition.

That he doesn’t look the part… well, he can’t help that. What is worse is that his Duca is nothing more than a silly macho man (what’s in a name?) and that his loud, in itself fine lyrical voice with solid pitch has only one colour.

Albanian Inva Mula really does her best to sing and look as beautiful as possible, and she succeeds wonderfully. All the coloraturas are there, as well as all those high notes. Her pianissimo is breathtaking, so there is nothing to criticise about that. But – it leaves me cold, because of how studied it sounds.

Marcello Viotti does not sound particularly inspired and his hasty tempi lead to an ugly ‘Cortigiani, vil razza dannata’, normally one of the opera’s most moving moments.

Leo Nucci and Inva Mula in ‘Si Vendetta’:

Gilbert Deflo

Sometimes I think that some opera directors have grown tired of all this updating and conceptualism and go back to what it’s all about: the music and the libretto. Such is the case with the Belgian Gilbert Deflo, who in 2006 in Zurich realised a Rigoletto that, were the story not too sad for that, would make you want to cry out for pure viewing pleasure (Arthaus Musik 101 283). He (and his team) created an old-fashioned beautiful, intelligent staging, with many surprising details and sparse but effective sets. The beautiful costumes may be of all times, but the main characters do not deviate from the libretto: the jester has a hunchback and the associated complexes, the girl is naive and self-sacrificing, and the seducer particularly attractive and charming.

Piotr Beczała, with his appearance of a pre-war film giant evokes (also in voice) reminiscences of Jan Kiepura. Elena Moşuc is a very virtuoso, girlish Gilda, and Leo Nucci outdoes himself as an embittered and tormented Rigoletto – for his heartbreakingly sung ‘Cortiggiani’ he is rightly rewarded with a curtain call.

Nello Santi embodies the old bel canto school, which one rarely hears these days.

Beczala, Nucci, Mosuc and Katharina Peets in ‘Bella Figlia del’amore’:

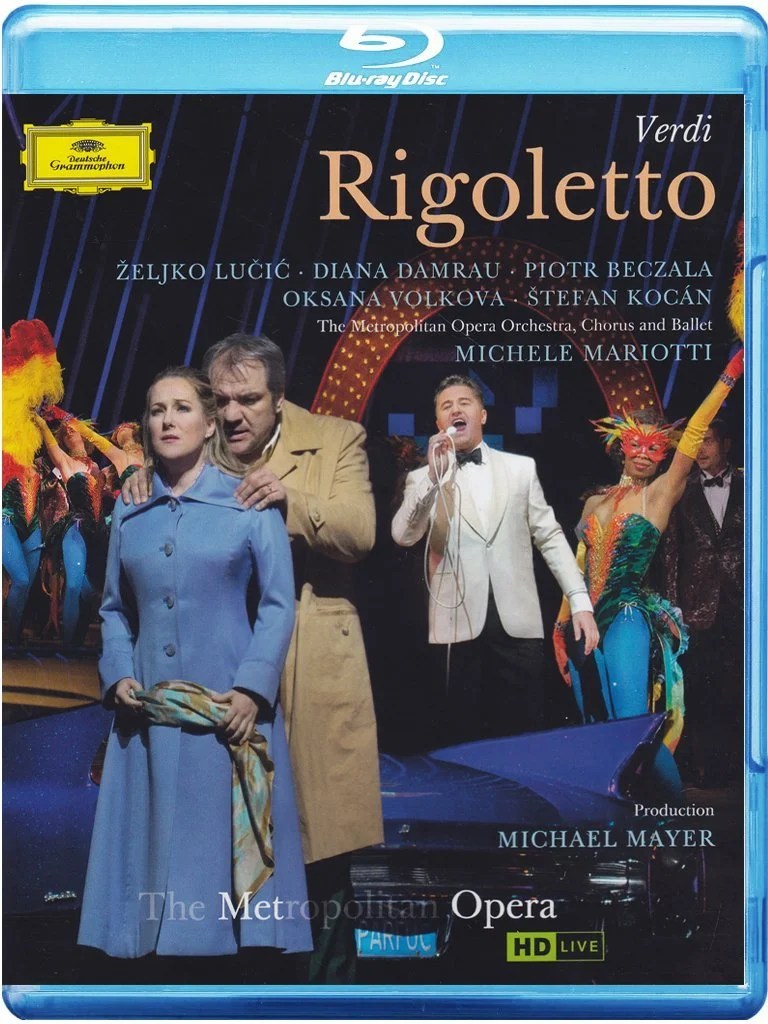

Michael Mayer

Times are changing and ‘director’s theatre’ has now also reached the New-York Metropolitan. They do not yet go as far as their European counterparts, but updating or moulding the libretto to a concept is now allowed.

In 2013, Michael Mayer made it a “Rat Pack ‘Rigoletto'” set in 1950s Las Vegas in which Piotr Beczała (Duca), armed with a white dinner jacket and a microphone, is modelled on Frank Sinatra (or is it Dean Martin?). Beczała plays his role of the seductive entertainer for whom ‘questa o quella’ are more than excellent.

Piotr Beczała sings ‘Questa o quella’:

Diana Damrau remains a matter of taste: virtuoso but terribly exaggerated.

Zjeljko Lučić does not let me forget his predecessors, but these days he is undoubtedly one of Rigoletto’s best interpreters. The young bass Štefan Kocán is a real discovery. What a voice! And what a presence! The production is fun and engaging, but you cannot deny that you often have to look far for the logic.