I had been playing with the idea of writing about modern American operas, because nowhere in the world is opera as alive as it is there. Romantic, minimalistic, dodecaphonic: something for everyone.

But ask the average opera lover (the diehards know Heggie, Barber and Menotti) to name an American opera composer: bet that they will not get beyond Philip Glass and John Adams. Why is that? Because we, Europeans, have a nose for American culture and feel superior in everything. That’s why

September 2018 it was exactly twenty years ago that an important American opera had its premiere in San Francisco: A Streetcar named desire by André Previn, after the play by Tennesee Williams. I was there.

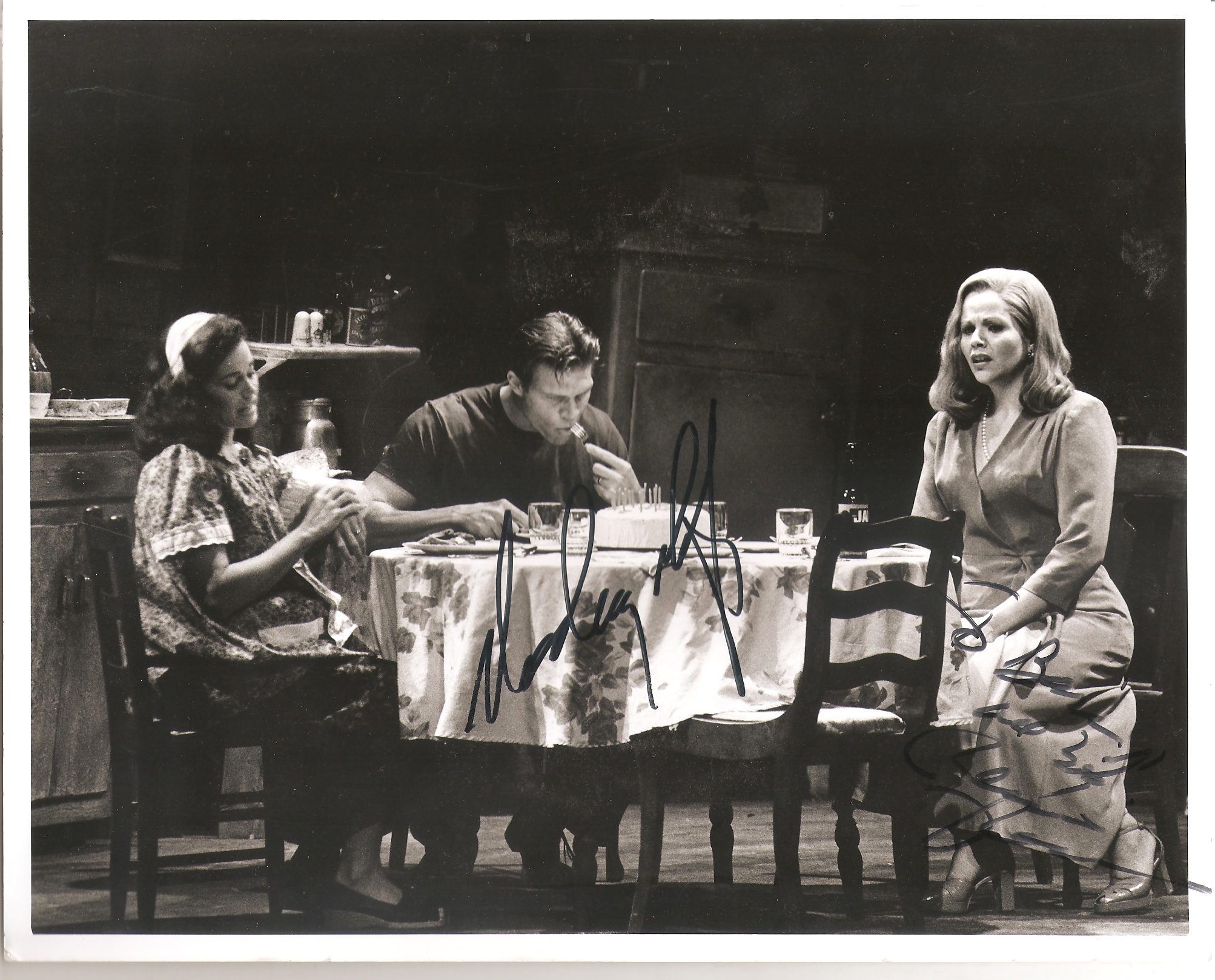

Elisabeth Futral (Stella), Rodney Gilfrey (Stanley) and Renée Fleming (Blanche) © Larry Merkle

THE PREMIERE

Expectations were high. Tennesee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire is one of the best known and most important American plays. Its adaptation by Elia Kazan in 1951 not only earned the play worldwide recognition but also a real cult status; and the main characters – curiously enough except for Marlon Brando – were all rewarded with an Oscar.

The play was made into a film twice more, without success. Not surprisingly, there are few films – or dramas – so intensely linked to the actors’ names. Still, it was the ultimate dream of Lotfi Mansouri, the then boss of the San Francisco Opera, to turn ‘Streetcar’ into an opera. Leonard Bernstein was approached but showed no interest.

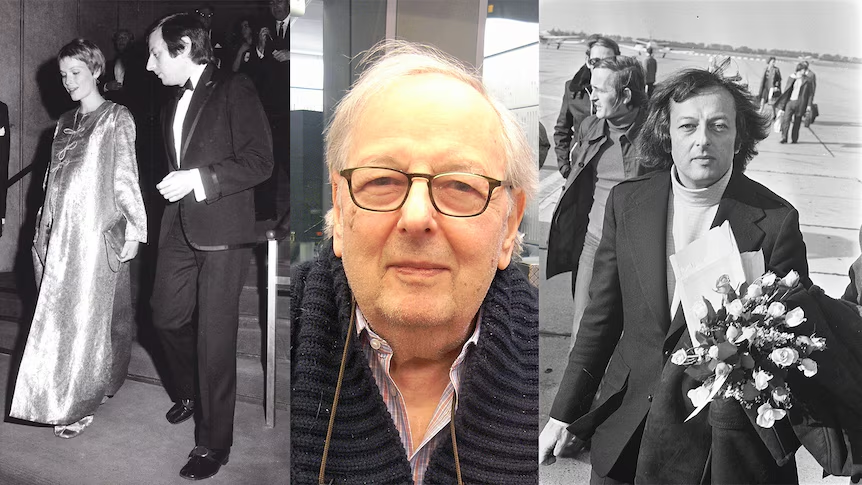

The choice eventually fell on André Previn, a choice that seemed a bit strange to some, after all he had never composed an opera before.

Philip Littel, an old hand in the trade, wrote the libretto. He was best known for The Dangerous Liaisons, an opera that premiered two years earlier with great success. Colin Graham was the director and for the leading roles, great singer-actors were cast.

The libretto closely follows the play and does not shy away from even the most difficult details. Small cuts have been made and Littel allowed himself a small addition: the Mexican flower saleswoman with her sinister ‘Flores, flores para los muertos’ returns at the end of the third act, with a clear message for Blanche. To me this felt slightly superfluous.

The stage images resembled those from the film. The first scene already: mist, a little house with the stairs to the upstairs neighbours and Blanche, carrying her little suitcase, singing ‘They told me to take a streetcar named Desire…” A feast of recognition for the film lover.

Renée Fleming sings I can smell the sea air:

You recognise fragments of Berg, Britten, Strauss and Puccini in the music, which is easy on the ears. The atmosphere is partly determined by strong jazz influences and you hear many trumpet and saxophone solos. Logical, after all, it takes place in New Orleans.

The opera is through-composed, but contains numerous arias: Stella and Mitch get one, there is a duet for Stella and Blanche, and Blanche herself is very richly endowed with solo’s. All attendees speculated what notes Stanley would get to sing with his famous “Stelllllaaa!!!

None, as it turned out. Rodney Gilfrey (Stanley), just like Marlon Brando in the movie stood at the bottom of the stairs and shouted. And just like in the movie Stella came back. The next morning she woke up humming. And she responded to Blanche with a beautiful big aria “I can hardly stand it”.

Elisabeth Futral (Stella) and Rodney Gilfrey (Stanley) © Larry Merkle

Elisabeth Futral provided a true sensation in her role of Stella. Blessed with a brilliant, light, agile soprano, she sang the stars from the sky and was ovationally applauded by the press and the public.

Stanley Kowalski’s role was Rodney Gilfrey’s own. He even did me, even if it had been forgotten Brando for a while. I don’t know how he did it, but he could sing and chew gum at the same time! He looked particularly attractive in both the torn white T-shirt and the “red silk pajamas”. Unfortunately Previn didn’t give him an aria to sing, which made him even more unsympathetic as a person.

Mitch was sung very sensitively by the then unknown tenor Anthony Dean Griffey, and Blanche….. André Previn wrote the role especially for Renée Fleming and you could hear that. Sensational.

Meanwhile Fleming has added her large aria ‘I Want Magic’ to her repertoire and recorded it in the studio for the CD with the same name.

https://my.mail.ru/video/embed/3374349646045150

CD

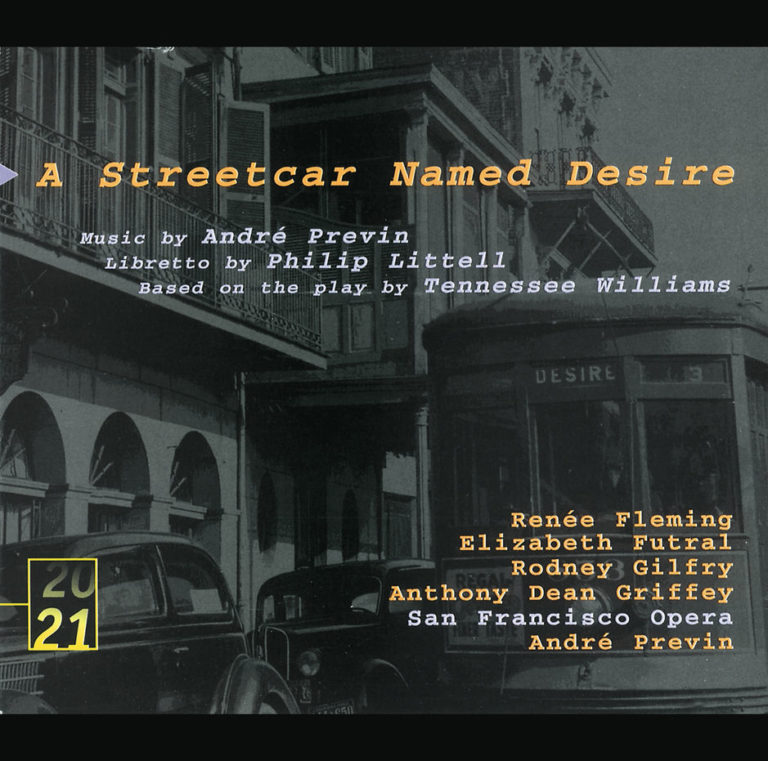

The opera was recorded live by DG and brought on the market in the series 20/21 (music of our time).

DVD

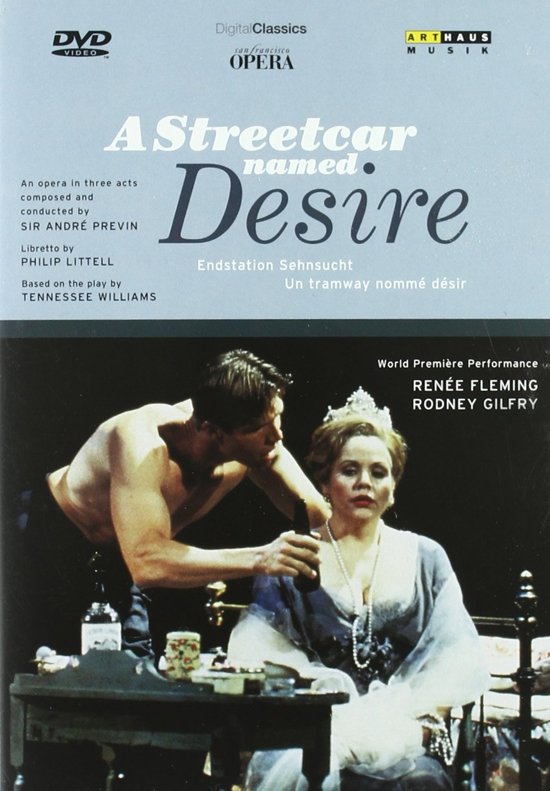

The opera has now become a classic and is performed in many opera houses in many countries, but the chance that you will ever see the opera in the Netherlands is virtually nil. Fortunately it was also recorded on DVD (Arthaus 100138). Not so long ago I have watched it again.

“Whoever you are – I have always depended on the kindness of strangers” sings Blanche Du Bois (Fleming), disappearing into the distance. She is led away by a psychiatrist, whom she sees as a worshipper.

Her words echo on, a trumpet plays in the distance, and strings take over the blues. The heat is palpable, the curtain falls and I look for a handkerchief. Before that I spent two and a half hours on the edge of my chair and even forgot the glass of whiskey I filled at the beginning of the opera.

People: buy the DVD and get carried away. It is without a doubt one of the best operas of the last twenty years.

Renée Fleming in conversation with André Previn about the opera:

THE KINDNESS OF STRANGERS

The kindness of Strangers’ is also the title of a film about André Previn, made by Tony Palmer

The kindness of Strangers’ is also the title of a film about André Previn