Richard Strauss and his fellow librettist Clemens Kraus gave Capriccio the subtitle “Konversationsstück für Musik”, which is exactly what it is: a long conversation. The subject of the endless conversations and discussions between the main characters is as old as the world itself:

which is more important, music or words? And it goes on and on, and on and on…

I have never been able to muster the patience to listen to it all the way through; for me, there was far too much chatter and too little action. Even the lovely sextet at the beginning of the opera felt too

long-winded to me. Anyway, you’ve probably realised by now that Capriccio is not one of my

favourite operas. And yet, even I had to give in! Although I must admit this was not wholly due to the music – which vies for the palm of honour with the libretto – but much more to the excellent singers.

And the direction: Carsen is very much like a magician: he would be able to transform even the dullest phonebook into a breathtaking thriller!

He moved the action to Nazi-occupied Paris in 1942, the time when the opera was first written. The entire Palais Garnier serves as the backdrop, including the majestic staircase, the long corridors and the boxes in the auditorium. I assume that video technology was used, but I don’t really understand it.

So I watch with bated breath as the Countess looks admiringly from her box at her alter ego singing on stage. A truly ingenious idea for the final scene, in which she originally had to sing her long final monologue in front of the mirror.

The final scene of the opera:

At the beginning of the opera, it is mentioned that the text and the music are like brother and sister, and likewise, the two rivals, the composer Flamand and the poet Olivier, end up sitting peacefully and brotherly together in the opera box, looking fondly at their joint creation: a symbiosis of words and notes: an opera!

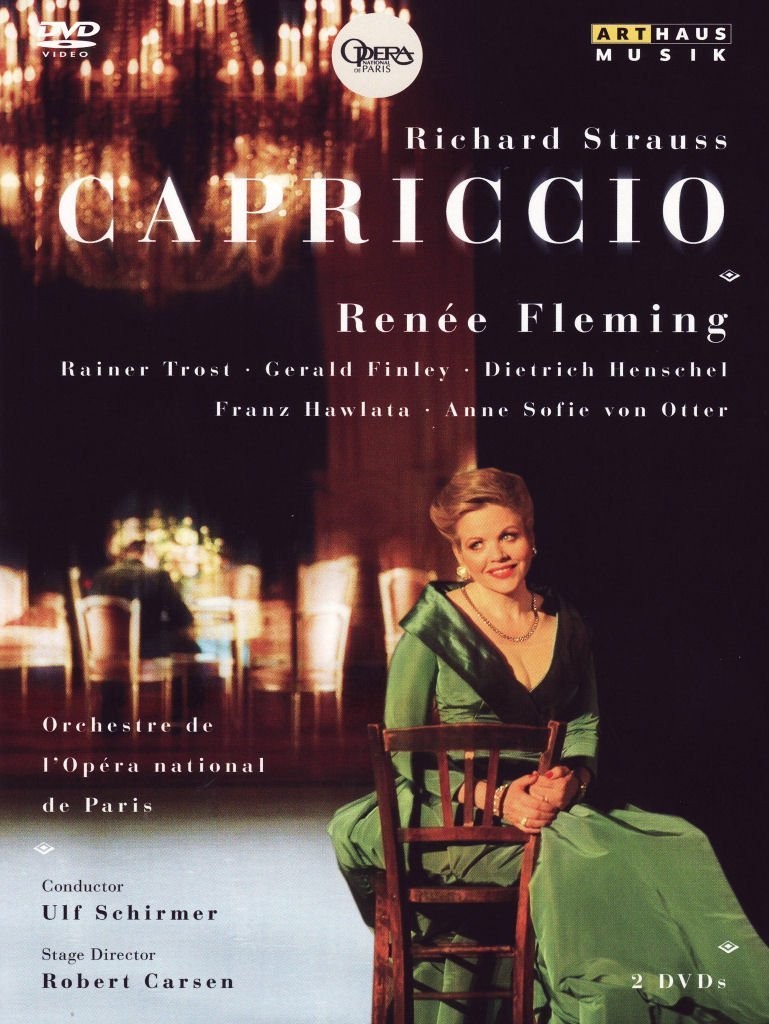

The Count (Dietrich Henschel) and Countess (Renée Fleming) in their Garnier box. DVD screenshot © 2004 Opéra National de Paris

It is hard to imagine a better Madeleine than Renée Fleming. With her endless legato, her round, creamy soprano and (not least) her stage presence, she portrays the Countess with narcissistic traits: beautiful, self-aware, aloof and highly admirable. Her brother, played by Dietrich Henschel, is her equal, and although he does not physically resemble her, his little traits betray the family ties.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to choose between the two gentlemen in love, because both Gerald Finley (Olivier) and Rainer Trost (Flamand) look very attractive in their smart suits, and there is nothing to criticise in either their voices or their acting.

Franz Hawlata is a phenomenal La Roche, and the delightful Robert Tear plays an entertaining Monsieur Taupe.

Anne Sofie von Otter is unrecognisable as the “diva” Clairon – whose big entrance, accompanied by a Nazi officer and with great fanfare, evokes memories of the great actresses of the 1940s.

Anne Sofie von Otter as Clairon with her companion. DVD screenshot © 2004 Opéra National de Paris

The direction is so brilliant that you simply forget that this is an opera and not the real world. Everyone moves and acts very naturally, and the costumes are dazzlingly beautiful. Were it not for the occasional prominent appearance of Nazis, one could imagine oneself in a utopian world of serene tranquillity.

Did Richard Strauss’s world look like this back then? Perhaps that was the message? I’ll leave the conclusion up to you.